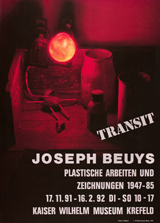

JOSEPH BEUYS

Dentro del conjunto de la obra de Joseph Beuys es fundamental la producción de ediciones o múltiples. La Galería La Caja Negra presenta una muestra de ediciones gráficas y efímeras compuesta por postales, carteles, serigrafías, litografías y grabados del artista alemán. Entre ellas, obras míticas como los Códices Madrid, Zeichen aus dem Braunraum o Der Schamane. Beuys, utilizando políticamente la reproductibilidad de las ediciones, las consideraba como la vía idónea para expandir sus teorías acerca del arte, de la función del artista y de su lugar en el mundo.

Probablemente Beuys sea el artista conceptual que con más insistencia haya intentado insertar su trabajo dentro de un todo orgánico regido por la libertad creativa y la coherencia estética. Para Beuys, cada individuo es un artista en potencia y debe explorar su propio lenguaje de realización. En sus ediciones está presente ese discurso globalizador en el cual el artista multiplica sus modos de ser y pensar convirtiéndose en ciudadano político, en místico, en científico racional, en poeta. La variedad de piezas que se exponen en La Caja Negra recogen la mayor parte de los símbolos discursivos de Beuys, al tiempo que reúnen las distintas instancias expresivas del artista: lo chamánico, la mitología animal, lo orgánico, la muerte, la denuncia social, lo público y lo íntimo.

Artista, profesor y activista político, Joseph Beuys nació en Krefeld en 1921. En 1940 fue piloto de un bombardero. En el invierno de 1943 su avión se estrelló en Crimea, donde los tártaros le salvaron la vida al envolverle el cuerpo con grasa y fieltro, materiales que aparecerán una y otra vez en su obra. Después de participar en diversas misiones de combate, fue hecho prisionero en Gran Bretaña desde 1945 hasta 1946. Posteriormente, Beuys estudió pintura y escultura en la Academia Estatal de Arte de Düsseldorf desde 1947 hasta 1952. En 1961, regresó a Düsseldorf para dar clases de escultura. Fue expulsado en 1972, por apoyar a los estudiantes radicales, pero fue readmitido seis años más tarde. Sus campañas a favor de la democracia directa, el medio ambiente y otras causas similares incluyeron la utilización de un local de la Documenta de Kassel en 1972 como oficina, la presentación de su propia candidatura para el Bundestag (cámara del Parlamento) en 1976. Su obra abarca desde performances como Coyote: I like America and America likes me (1974), en la que convivió con un coyote en una galería de Nueva York, hasta esculturas como El final del siglo XX (1983), consistente en 21 piezas de basalto taponadas con grasa, uno de sus materiales recurrentes. Murió en Düsseldorf el 23 de enero de 1986.

— Arte10

El último romántico

El mito del genio creador, de profeta del arte, tuvo en el alemán Joseph Beuys uno de sus grandes representantes en el siglo XX. Un conjunto de sus pequeños trabajos sobre papel, reflejos de su mundo íntimo, se presenta ahora en Madrid.

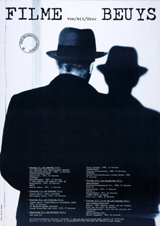

Joseph Beuys (Krefeld, 1921-Düsseldorf, 1986) se convirtió a partir de los años sesenta en una obra de arte viviente. Su carismática figura, su presencia física, su imagen fotogénica, sus palabras, sus gestos y (sobre todo) su firma se convirtieron en obras de arte reconocibles e inconfundibles. Con él culminó el Romanticismo alemán, el mito del genio creador, la interpretación del artista como heraldo del más allá, como chamán o sanador de una sociedad corrompida. Esta "novela del artista" se fue desglosando en obras de una megalómana antimonumentalidad, realizadas con materiales heterogéneos, toscos y maleables que adoptan formas imprecisas y espontáneas pero, sobre todo, esa vida se manifiesta en un sinfín de dibujos, acuarelas, grabados, litografías, serigrafías, carteles, tarjetas, fotografías y pequeños objetos que reflejan su mundo inmediato y cotidiano, con los que ha extendido sus actos y sus ideas por medio de múltiples ediciones, de las que ahora se presenta esta breve muestra. Se trata, en muchos casos, de pequeños papeles que parecen desgarrados al azar sobre los que el artista ha dejado una huella esquemática, formada por trazos contundentes que perfilan toscas figuras de un bestiario personal formado por animales, como liebres, pájaros o renos, que se acompañan con un cuño y la firma del artista. Su aportación al arte de la posmodernidad se concreta en un simbolismo discursivo y egocéntrico que recrea en piezas pequeñas e íntimas que se han convertido en reliquias capaces de engendrar la mitología de un creador liberado de cualquier atadura técnica, social o estilística. A pesar del aspecto primitivista, expresionista o matérico de que hacen gala la mayoría de sus obras, el éxito que éstas han obtenido se apoya en las técnicas de difusión del pop art, que Beuys toma directamente de su amigo Andy Warhol, y en las atractivas ideas de promoción de una "democracia directa", con tintes ecologistas, teorías que difundió desde la atalaya de su cátedra de escultura en la Academia de Düsseldorf.

— El País

‘I did take the role of the shaman ...’

the artistic rituals of Joseph Beuys

The relationship between the notion of ritual and the work of the German artist Joseph Beuys seems self-evident and questionable at the same time. In this essay, a reflection on the notions of ritual and of theatre/performance art will be followed by a description of the ritualistic allusions in Beuys’ work. As an example of ‘artistic rituals’ I discuss Beuys’ performance Celtic +~~~ which took place in Basel (Switzerland) in 1971.

Thinking about the German artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) and the notion of ritual brings up a paradoxical situation. On the one hand there seems to be a strong connection. Beuys—allegedly rescued by native Tartarians after an air crash in the Second World War—can be seen as the artist who tried to work out a holistic concept of art and life in answer to the crisis that Europe, and particularly Germany, faced after 1945. To this effect he studied Asian worldviews, Celtic myths, and Christian symbols. The concept of ritual appeared both in his reading and in titles for drawings or objects. It also was an obvious model for his performances, where he played with the attitude of the shaman. Hence, many spectators described their experience of Beuys’ works in ritualistic terms, or in terms of a ‘rite of passage’.

On the other hand, Beuys’ concept of art met with harsh criticism from conservative politicians, left-wing art-critics, and well-known colleagues. Especially the American art-historian Benjamin Buchloh elaborately criticized Beuys’ idea of the artist as a leader, pointing out that the artist sees himself as a ‘privileged being, a seer that provides higher forms of transhistorical knowledge to an audience, that is in deep dependence and need of epiphanic revelations.’

Once again, the case of Joseph Beuys seems to bring up the question of art and ritual in a broader sense. What are the reasons to look for rituals as sources for modern performances? To what extent does the notion of ritual influence the image of post-war artists? And how can we describe art forms that are meant to cross the border of theatrical representation through ritualistic practices?

Correspondences and Differences

As recent publications have shown, there is a wide range of definitions to describe and explain rituals. They can be seen as ‘processes of embodiment’, as ‘symbolic actions,’ or as ‘cultural performances.’ These divergent concepts overlap in at least two points: rituals are transformative actions, based on traditional patterns.

As transformative actions, rituals generate a natural or social transformation or change. Arnold van Gennep showed in his description of ceremonies surrounding birth, death, and marriage that such rites change the social role and the status of a subject. Even while rituals are cultural mechanisms to overcome a difficulty or a crisis, they do not merely have a stabilizing function. They can unfold transgressive energies and violent conflicts, by triggering a state of ‘liminality’, i.e., a zone of ‘betwixt and between.’

Rituals follow traditional patterns of action, which have to be reiterated in every performance. As modern theories pointed out, these repetitions are always reinventions of a fixed scheme, which can vary to a certain degree. The ludic and playful elements of rituals may include various materials, sounds, gestures, actions, and linguistic signs.

Therefore ritual and theatre have a lot in common. Both are cultural performances, which are linked to the presence of human bodies. In both cases people are taking up certain roles and following a mise-en-scène. Both can trigger individual or collective effects.

But while rituals need to be done by authorized persons and in a traditional setting, theatrical performances are open to artistic shifts and different interpretations. In that sense, the performative quality of a ritual differs from that of a theatrical play. While the wedding ceremony in a Christian church (effected by a priest) changes the status of a man and a woman into a couple, the same ceremony played on a theatre stage could not generate a new social reality.

When we look at the history of performance art, it is interesting to note that the theatrical allusions to ritual at the beginning of the twentieth century (as we find in the works of Antonin Artaud, Georg Fuchs, or the Ballets Russes) are inspired by an interest in the ritual’s performative quality. Throughout a ‘ritualization’ of theatre (as Richard Schechner called it) the performance should transform the audience into a community and open it up to spiritual energies. When, during the sixties, the idea of ritualization re-entered the field of modern art, it was derived from two sources: the artistic desire for strong sensory experiences beyond the domain of traditional art, and the lack of a suitable terminology for the new art forms.

It is remarkable that an artist like Allan Kaprow, commonly known as the ‘inventor’ of an art form called ‘Happening’, tried to define it using ritualistic terms. He argued:

Happenings, freed from the restrictions of conventional art materials, have discovered the world at their fingertips, and the intentional results are quasi-rituals, never to be repeated.

As much as the idea of an unrepeatable ritual is an oxymoron, Kaprow’s Happenings do have affinities with cultural performances such as ‘parades, carnivals, games, expeditions ... and secular rituals.’

While Kaprow uses the term ‘ritual’ or ‘quasi-ritual’ to describe a formal structure of performance which will no longer be ‘staged theatre’, his European colleague Joseph Beuys seems to justify the notion of ritual in a different way. Beuys’ work appears to be inspired by various mythological traditions, by symbolic elements, and by the idea of shamanism.

Ritualistic Elements in the Actions of Beuys

Beuys rarely uses the term ‘ritual’ to designate his own work. But his theoretical writings and his art works are full of elements that we know from a ritualistic context. I would like to point at five distinct elements.

(1) Mythology: The Celtic mythology remained an inspiration throughout Beuys’ life. It is very prominent in the idea of ‘Eurasia’ (the name of several performances, films, and objects) as a combination of European and Asian spirituality. By working with a coyote in New York in 1974, on the occasion of the performance entitled Coyote: I like America, and America likes me, the artist also tried to bring in the narratives of the Native Americans. Beuys combined these mythological traditions with his own private mythology, in which the crash of his airplane during the Second World War introduced him to the way of life and the culture of the nomadic Tartarians (close to the Mongolian border).

(2) Christianity: The Christian iconography can be seen as another source for the artist’s work. He reinterpreted the symbol of the cross by reshaping, splitting and transposing its beams. Beuys’ idea of what he calls the ‘Christusimpuls’ as an inspirational power which realizes itself through the act of suffering can be seen as a desire to transcend human nature. As we will see later, we can find symbolic actions—like baptism and the washing of feet—as formal elements in his performances.

(3) Animality: One of the very early distinctions between the Fluxus movement and Beuys (who is strongly connected to Fluxus during the sixties) concerns his use of dead or living animals. In the performance Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt of 1965 (How to explain pictures to a dead hare), Beuys was sitting in a gallery with a golden layer of make-up on his head, speaking incomprehensible words to a dead hare on his lap. In the same vein, the living animal from Coyote was also supposed to function as a bridge to the forgotten spiritual realm of early America. Lastly, Beuys frequently made use of bones from dead rats, hares, or cows in order to connect to shamanistic rituals, in which remains of animals often play a central role.

(4) Transformation: As much as transformation is the aim of a ritual, it also applies to the artist’s work. Transformation means to transfigure objects or actions by revealing their inner energies. Therefore Beuys often employed organic materials (fat, felt, blood, or eggs) that are transformed during the process of decay. Transformation equally refers to changing the spectator or the audience, who should reach a higher state of mind by means of the aesthetic experience. As much as Beuys wanted to trigger an evolutionary process, his notion of ‘development’ has always been understood as a transformation to higher states of conciousness and existence.

(5) Habit: Finally, there is the idea of Beuys as a leading figure, a ‘Hirschführer’ (literally: deer leader) or a shaman. Here it becomes evident that the artist functions as a medium, a connection to the transcendent levels of reality. Beuys embodied that role by wearing special clothing (a fur coat, his hat, his waistcoat), which is not merely a costume, but also functions as everyday clothing. It can be seen as a way of self-fashioning (a term introduced by Stephen Greenblatt): the creation of a self according to different visual and vestimental standards.

In Beuys’ own words, the allusion to shamanistic fashioning and practice gives the possibility to overcome the dissociated world of now:

I did take the role of the shaman. But not in the sense of pointing backwards, in the sense of ‘we have to go back’, but to express something futuristic/utopian. The shaman symbolises someone who brings materialistic and spiritual relations into a unity.

Taking ancient elements to achieve an utopian state—as Beuys’ words suggest here—is characteristic for the re-theatricalization or re-ritualization the avantgarde and neo-avant-garde promoted. Achieving a collective and artistic unity—as the idea of a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ suggests—can only be reached by acts of transgression. In this sense, taking the role of a shaman seems to enable the artist to function as a medium between here and there, the perceivable material world and its hidden spiritual forces. Beuys’ interest in transgressive actions is always motivated by the search for an ‘anthropological art’, or an ‘organic society’. He tries to initiate a ‘healing process’.

Critics of these ideas should be aware that a certain distance remains between the performer (artist) and his role (shaman), and between an artistic performance and a true ritual. As Gabriele Brandstetter claimed for Strawinsky’s Le sacré du printemps, reading the performances strictly as a ritual would not justify their complexity, because ‘it is not a mise-en-scène of a ritual but rather (...) the staging of a portrayed ritual’.

In order to reveal some of the aesthetic strategies and effects in Beuys’ artistic rituals, I would like to discuss his performance Celtic +~~~, which took place in Basl (Switzerland) in 1971.

Celtic +~~~

In April 1971, Beuys executed a performance named Celtic +~~~ in Basl. The socalled ‘action’ lasted about seven hours and was performed in an air-raid shelter under construction. At that time, the German artist was already quite famous, and so the bare space at the periphery of Basl was temporarily filled with more than 700 people.

During the entire performance, music by the Danish Fluxus composer Henning Christiansen was played. I would like to give a short impression of the performance, which is entirely based on filmed documentaries, photographs, and the book on Beuys’ performances by Uwe Schneede. During most of the performance Beuys moved right through the audience, executing several actions involving various objects and instruments. He started by washing the feet of seven people, then drew symbols and letters on a blackboard he showed to the audience. He pushed his way through the crowd by slipping the blackboard on the ground.

Then four of Beuys’ experimental movies, in which former performances and landscapes were shown, were projected on the concrete walls of the shelter. For more than one hour, Beuys collected small pieces of gelatine from the walls, which he had prepared before, while climbing up a stair and balancing a big plate on his shoulder. After spilling all of the gelatine over his body, he made ‘öö’-noises into a microphone, a sound reminding of the bell of a deer. At this time the action had already lasted for six hours, and many of the curious audience members had gone home. Then the artist stood still for about an hour. Holding a tall wooden stick in his right hand, he remained silent, surrounded by some one hundred people in the centre of the shelter. While monotone sounds filled the air, the audience seemed to meditate together with the performer. Suddenly tears ran out of Beuys’ eyes—not accounted for by any action of the performer. He finished the performance by kneeling down in a tub, and posing in a gesture of prayer. Henning Christiansen was pouring water over him. Beuys stood up, laughed, and said ‘finish’.

I would now like to investigate two aspects of Celtic +~~~ that relate specifically to its ritualistic dimension, namely, the performance’s frame of reference and the different roles the performer takes on.

(1) Framing. The footwashing scene at the beginning and the baptism scene at the end set the action in a ritual frame. This assumption is supported by the fact that Celtic +~~~ took place in the week before Easter. One may suppose that the attentive Basl population recognized the washing of feet and the baptism in the tub as Christian ritual elements. Because Beuys claimed that his action constituted ‘eine tiefgreifende Transformation, Metamorphose (...) eine Umwandlung des Begriffes [der Kunst] selbst,’ it has been said that Celtic +~~~ is itself an initiation ritual. The place of the initiated would then be taken by the concept of art—which cannot exist without a conscious mind thinking of it—or rather by the participants themselves, who have been invited throughout the action to transform the concept of art into a more ‘anthropological’ notion.

Nonetheless, Beuys’ action is not a ritual, because the different action sequences are performed within the framework of an artistic event, which may quote rituals and refer to their meanings and structures, but cannot effect the change of status which is an essential part of ritual as a cultural performance. Ritualistic moments only function within this action as quotations of symbolic meaning, and as cultural references.

(2) Roles. On a symbolic level, we can identify different roles, such as the figure of Christ (in the baptism and washing sequence), the role of the herdsman/ shepherd (walking through the crowds with the wooden stick), the role of an animal (crawling on the floor), the role of a guard (referring to Parsifal), or the role of a collector (during the action where he gathers pieces of gelatine from the walls).

By representing such different roles various religious, mythical and aesthetic contexts are juxtaposed and blended. If we follow this description of personas, we may similarly identify a list of roles adopted by the audience. They are, first, the Apostles or followers of Jesus, or a Christian community witnessing a baptism; next, a herd of sheep; thirdly, a swarm of animals; fourthly, the knights of the Grail, and so forth.

The question remains if the audience had read these roles into the actions, and did consciously adopt them. But even if they did, it was not enough for them to impersonate an attributed role affirmatively. Rather, the participants created and displayed the roles they chose for themselves, such as the role of ‘troublemakers’ performed by students who disturbed the action and distributed anti-art-leaflets, or the role of an annunciator, performed by a young lady who suddenly climbed the piano, shouting ‘Bitte machen Sie Platz, der Herr Beuys kann ja nicht atmen.’ The multiple creation of roles turned the relationship between the audience and the artist into a permanent play – or even a struggle.

Conclusion

The performance Celtic+~~~ shows diverse modes of action that are reminiscent of the liturgy of the Catholic Mass: the Orans gesture of prayer (baptism sequence) as well as the gesture of demonstration (the blackboard action, and the gelatine sequence). Beuys refers to the repertoire of Christian iconography by sequences of actions, in which he performs distinct and concentrated gestures. Critics have interpreted these acts of the artist as a figuration of Christ. Beuys was dubious about such notions of aesthetic embodiment. For him, it is clear that he did not impersonate Jesus, but that he tried to refer to a ‘Christian impulse.’ To the extent that Beuys insisted on the very process of doing and of performing—and in relating these to religious acts—we can understand his deeds as a ‘profanation.’

As Giorgio Agamben has recently argued, profanations are reinterpretations or inversions of that which has been separated from life. The religious is a prime example of such a separation. A profanation is the playful use of something thus separated as the canon of sacred forms. This playful use frees the sacred object or act from the taboos that surround it, such as touching the sacred object or performing the sacred gesture in an improper context. Thus, the new form of use is reintegrated into the sphere of living coherence. This use is not the same as the utilitarian consumption of goods—it ‘does not signify the lack of care (...) but rather a new dimension of usage.’

Consequently, only the performative employment can dissolve the traditional sacral contexts of meaning from an object or an act. Profanation may stimulate new modes of perception and interpretation.

Barbara Gronau

— zombrec

Movements of Avant-garde Art

The term ›avant-garde art‹ does not designate a uniform concept; rather, it embraces a collection of diverse movements, styles and experiments. Their common focus is the »withdrawal of art from art« (Joseph Beuys). Its pathos derives from an explicit repudiation of the art of the past - especially the art of the classical and the Romantic periods - a revolt against the idea of art, its identity, its symbolic order and the institution of art. Inherent in the art of the avant-garde there is a law of reflection - in the Hegelian sense - forcing it into unceasing contradiction with itself. »It must turn against that which constitutes its own concept,« says Theodor W. Adorno in his Ästhetische Theorie, »and in so doing it will become uncertain right down to the very fibers of its being. It is not, however, to be dismissed as an abstract negation. By attacking that which the entire tradition considered to be guaranteed, the bedrock on which it stood, it transforms itself qualitatively; it turns into another.«

The aesthetic process of the avant-garde therefore does not consist as much in an ›innovation‹ in progress - the extension of the language of images, the use of new techniques and materials - as in a ›destruction‹. In the Heideggerian sense, this does not mean a demolition, but a ›dismantling‹ of the traditional stocks of metaphysics and aesthetics; in the ruins are to be found other fundaments upon which art can be established anew. In so doing, it carries out a radical transformation of its being. The artistic avant-garde no longer create ›works‹ that denote something, represent a scene or reproduce a mood, rather its manifestations are signs that refer first and foremost back to themselves. Its aesthetic becomes self-referential and thus, step by step, cancels out the constitutive conditions of the art of the last four hundred years: its autonomy, the subjectivity of the expression ›mimesis,‹ the means of representation, the artist’s conception of himself as magister operis, master of works, the singularity of his creative achievement, form, poiesis, the temporal mode of permanence, of the museum’s stocks, of eternal value (Walter Benjamin).

»The sculptural avant-garde reacted to the dissolution of the painter’s craft by embarking on a search focusing on the question, ›What is painting?‹« according to the catalogue of the Immaterialités exhibition in Paris in 1985, organized in collaboration with Jean-François Lyotard. »The premises and prerequisites for the exercise of this métier were put to the test one after the other and thrown into question: local colour, linear perspective, quality of reproduction of the colour tones, framing, format, base, medium, tools, exhibition site and many other assumptions were graphically questioned.« The same applies for music and poetry when they disrupt the order of tonality and its notation or the meter, rhythm and linearity of poetic language.

The characteristic feature of the art of the avant-garde is thus the constitution of an art ›about‹ art. It becomes systematically caught up in a discourse with itself; a structural paradox is inherent in it. This paradox consists in the thematisation of its own immanent codes, based on and applying precisely that syntax and semantic that it thematizes. The break that it enacts is a rupture in itself: this renders access more difficult and explains the furious rebuffal - of its projects and actions, its denunciation as »non-art,« as absurd provocation or merely an expression of the degeneracy of culture. But its paradoxical structure accords with the difficulty of the transition itself, the endeavour of an art against art that always has yet to overcome that which enables its destruction. The paradox therefore does not bear witness to the failure of the avant-garde, its necessary self-obstruction, but rather to the dynamics peculiar to its self-liberation.

This liberation is not enacted in a linear fashion; rather, it takes place as renewed endeavours, initiatives and metamorphoses that try to intensify the crisis of art and to overcome it at the same time. Herein lies the specificity of the logic of the development of avant-garde art. Its objects and interventions are ›destructions‹ in that they venture to penetrate anew to the foundations of the aesthetic, in order to dissolve them again the next moment. All the concepts of the artistic avant-gardes are double-faced: they evince themselves productive to the same extent as they are destructive - productive in destruction and destructive in production, in that they seek to attach their work of critical decomposition to points that at the same time offer visions of a new aesthetics. These concepts can be described in the vocabulary of classical antiquity, aisthesis, askesis and ekstasis, and through the recovery of the auratic that modern art lost by becoming detached from rite, according to Walter Benjamin’s diagnosis. It is to the very rigour with which the avant-gardes carry out the destruction that they owe in turn their radical drive in taking up these points.

II.

The early modernities - Expressionism and Fauvism - do not yet proceed in a manner that is properly avant-garde; nevertheless, they do belong to the ›archaeology‹ of the avant-garde. Without exception, they retain the style, frame and subject matter of the traditional aesthetics of the work of art, and yet they already ensure its consistent deretrenchment [Entschränkung]. The concentration of that which is represented, the deformation of the figural, the distortion of space and perspective, and the detachment of colour from its former function of representation all belong to the category of deretrenchment. The early modernities therefore carry the subjectivity of expression and the mimetic too far, right to their inner limits, as in the transition from tonality to atonality in the New Music. Everything about Expressionism is intensification, augmentation; painterly in the Cubist paintings of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, compositional in the twelve-tone techniques of Arnold Schönberg, its intensity is heightened and finally transcends the dividing line to autonomy of structure. Henceforth art, in accordance with the aesthetics of Paul Valéry, becomes pure »construction.«

No longer is art subordinate to the sovereignty of the gaze and its mimetic order; on the contrary, paintings become planes composed of elementary geometric forms and figures - lines, circles, triangles, squares, spheres and so on. Cubism therefore does not represent but instead replaces the ratonality of representation with a variety of symbolic structures and geometries. Breaking with the logic of central perspective, it opens up a multitude of possible organizations of the picture, but its reference point - as in Juan Gris’ Gitarre (1913) or Braque’s Bouteille et journal (1911) - remains an object or an ensemble of things. Like twelve-tone music, it turns out to be an aesthetic constructivism that does not refer to art as art reflectively, but merely to the multitude of possibilities of constructing the world. »We are living in an epoch of art,« wrote Pierre Reverdy about Cubism, »in which stories are not told in a more or less comfortable way, but rather in which works [...] that lead their own existence are produced.«

If Expressionism and Cubism maintain the continuity of traditional aesthetics by retaining its central relation between image and reality, the early avant-gardes, Futurism, Dada and Surrealism, rupture that continuity. Their programmes are articulated in the form of staged manifestos and proclamations. They are part of their own rhetorical self-acclamation which, like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s First Futuristic Manifesto, relentlessly ›declares war‹ on art, without having a new one to offer. The theatricality of its appearances is a symptom of embarassment. The Dadaists in particular set off veritable fireworks of manifestos and anti-manifestos which were already equal to the first Happenings in the degree of their provocation. »Everything is Dada. Everyone has his Dada. [...] Dada is neither a literary school nor an aesthetic doctrine. [...] Dada destroys and is content with that.« Thus the Dadaist Manifesto saw itself as primarily negative; it took its stand on the border of art, it was entirely action, spectacle, ridicule of the bourgeois, even performative self-nullification that strived to confound all of aesthetics’ concepts. Its literal non-sense signified the refusal of every question about the meaning of art.

Yet in the end, it remained empty iconoclastic, because an alternative was lacking. That alternative was established in Surrealism, along the opposition between rationality and fantasy. In this way it created the first ›language‹ of the avant-garde, out of which - overcoming it - a plethora of further projects were to arise: Assemblage, Frottage, Environment, Action Painting, etc. The objective was to settle accounts with what André Breton called the »abhorrence of the marvellous« in his Surrealist Manifesto of 1924. His intention was to deliver us from that abhorrence by liberating the unconscious from the fetters of consciousness and reason with the aid of the psychoanalytic techniques of free association and automatism, in order to return art to its origins in dream and imagination. »We are still living under the sway of logic,« he continued, »perhaps the imagination is on the point of reentering into its rights.«

All the properties of avant-garde art can already be discerned: its rigourous challenge to art, its self-referential trait, its destructive dynamics, and lastly, its search for an origin, a new determination of aesthetics - destined solely to be surpassed by future developments and swept away.

III.

It is only with the intervention of abstract painting that the process of the avant-garde sets out on its self-seeking course. Already at the turn of the century, Maurice Denis had announced that every work of art was in essence a flat surface covered with colours before it became a naked woman or an anecdote. Wassily Kandinsky accordingly described the picture as a »combination of pure colour and independent form« and proponed the emancipation of the »composition of colour and form.« This emancipation had already taken place with the exhibition of Casimir Malevitsch’s Black Square on White Ground in 1915: the picture exemplified the negation of the picture, became self-reference, tautology. It is what it is, like Lucio Fontana’s stroke or pure line, or Josef Albers’ Hommages to the Square, multiple responses to Malevitsch (since 1949).

What is crucial is the context of the discussion that the individual productions engender: a complex discourse of art in which the pictures and objects react to each other and comment on each other reciprocally. The structure of the dialogue necessitates the radicalization of the analysis: thus the suprematistic compositions of black, red, yellow or blue forms structured according to strict geometrical dimensions follow Malevitsch’s Black Square. Kandinsky would create complex symphonies of spaces, surfaces, figures and unmixed colours, crossing them with organic shapes. The composition is the mystery of free balance, for Paul Klee, poetry of rhythm and sound. Finally Piet Mondrian reduced the entire picture to its individual components: to the vertical and the horizontal and the three primary colours, red, yellow and blue on a white surface, and synthesized them into designs of simple harmony. The process of analysis ends with abstract Expressionism and Barnett Newman’s large monochrome later works from the series Who’s afraid of red, yellow and blue (1967-68) polemically turning against Mondrian, or Ad Reinhardt’s silent black tableaux.

The development has by no means reached an end, but it is stagnating, repeating itself, and only introducing nuances at best - like Gotthard Graubner’s colour-space-bodies or the endless rows of white canvases crowding the exhibition halls right up to the late Seventies. Yet the endpoint of the emptiness opens up into quite a different one: Already Barnett Newman’s surfaces of colour overcame the materiality of the picture in favour of mere colouredness as meditative space. The picture as mutilated language becomes absolute presence and in precisely this way refers to a transcendency that cannot be symbolised: »infinity, strictly speaking, is monochromatic, even better, colour laid bare,« remarked Piero Manzoni about his sequence of unalloyed white pictures, »for me, the issue is to render an entirely white (or, better, entirely colourless, neutral) surface, outside of all painted appearance [...]: a white that that is not a polar landscape, nor an object of association, not a beautiful thing, not a feeling, not a symbol or anything else: a white surface that is a white surface.«

In this way, in the midst of the dissolution of the concrete, another form of seeing opens up: perception itself, that is no longer perception of something, but rather the gaze without intent that arises out of the emptiness of meaning and for that reason is essentially contemplation. It is linked to the original meaning of aisthesis: the appearance of that which, of itself, shows itself. It was for this reason that Lyotard, like Barnett Newmann himself, had recourse to the category of the »sublime,« in order to release modernity from the tyranny of the »beautiful.« The experience of the sublime, according to Immanuel Kant, is based on an ambivalence which is not to be resolved, because the imagination fails in its attempt to conceive of the great as such [das schlechthin Große], and Reason celebrates the idea of the infinite in it. In this sense, the large monochromatic planes of colour confront the unrepresentable as such: they are ›emanations‹ of pure aesthetic experience and as such, they recall to mind the mystical that had got lost.

IV.

Surrealism raises not only the question as to the constitutive elements of a picture, but also and in the same measure, as to the creative act, the process of design, the aesthetic imagination - in short, the question as to the subject as opposed to the object of art. This question is not posed in abstract and monochrome painting; in this way, the avant-garde advances from the destruction of the picture to the destruction of the artist.

It is already prepared for by Dada’s accidental products, for example, Jean Arp’s Ordonné après la loi de la chance, aussi nommé points et virgules of 1944, but also Max Ernst’s dessins automatiques. That which they have in common is the systematic eradication of creative subjectivity. The picture invents itself, independently of that which the artist had wanted or had been able to do at the time, and it erects its own, non-intentional order. The same effect is later achieved by Wols and ›Action Painting,‹ through the unremitting exaggeration of aesthetic spontaneity at the moment of its excess. It is not ›something‹ that becomes thematic in the picture, not even the picture as picture, but the pure corporeality of the act of painting or the hand movement with which a line is drawn and scratched out, paint applied, smudged or thrown onto the canvas. In so doing, the production of art makes itself into the object of experience, raw and coarse in Jackson Pollock and Georges Mathieu, subtle and calculated in Cy Twombly. The picture thus becomes a non-picture, a surface upon which something takes place, a tableau on which inscriptions are made, during which the whole body is called upon and must exhaust itself or discipline itself. It was therefore logical that Roland Barthes should borrow the description for it from the language of the theatre: the canvas is like scenery that permits a variety of types of event: »a fact (pragma), a coincidence (tyche), a starting point (telos), a surprise (apodeston) and a plot (drama).«

Gesture and means are given primacy, while the result itself becomes unimportant and functions, at best, as the protocol of an action or of a creative delirium. Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy of the Dionysiac and Georges Bataille’s aesthetic of ecstasy now enter onto the stage: the aesthetic process takes place beyond all control and direction, as the adventure of the exhaustion of self that the artist, acting for us, takes upon himself. And yet such extreme subjectivization of art only prepares its inversion, its complete de-subjectivization. This was carried out, most radically perhaps in the New Music, through the transition from Serialism to Aleatoric and the chance compositions of John Cage; in painting, de-subjectivization took the form of the extinction of all traces of individuality in Concept Art. The idea is the »machine [...] that does the work« said Sol LeWitt. It is not the artist who creates something, not the composer who converts his ideas to tones or sounds; rather, it is a structure »beyond the subject« that paints and discovers its own pictorial or musical universe. Nothing can be questioned or interpreted in respect to a will or a conclusive expression: chance confronts the unavailable. It ›is‹ and files a claim for its innocent presence, independent of all principles of taste and the truth. »I have never heard a rotten sound, not one!« avows Cage in his conversations with Daniel Charles: chance forces the asceticism of its acknowledgement on us. Askesis means practice; it concerns here the surrender to the unavailability of that which takes place each time. It is not that it bases itself on a passivity, but rather demands the utmost concentration and attention. The endeavours of the avant-garde end in an aesthetic of »letting be« [»Seinlassen«] and of imperturbability [»Gelassenheit«] (Heidegger). This new aesthetics goes hand in hand with another way of living that is reminiscent of the serenity of Zen Buddhism.

V.

The cultural revolutions of the Sixties, revolt fermenting everywhere, give impetus to the process gathering speed in another headlong rush: art breaking out of itself. It leads to that famous diagnosis of Adorno’s at the beginning of his Aesthetic Theory, that as far as art went, nothing was to be taken for granted any more, »neither in it nor in its relation to the whole, not even its right to existence.« This diagnosis is based on the dissolution of all dichotomies sustaining the philosophy of art - the differences between art and non-art, between high and low culture, between fine art object and banality, between politics and aesthetics - that constitute what was previously their concept. In contrast, a plethora of new stocks emerge: pop art, Installation and Environment, Happening and Fluxus, Concept Art, Action Art and Performance, but also a »longing for pictures.« A confusing chaos of disparate and mutually contradictory directions and tendencies have come into being since the Seventies, giving rise - not just in the domaine of aesthetics - to the term »new obscurity« (Jürgen Habermas).

At first, Dadaism and Surrealism continued to form the points of reference whose multiplicity of inspirations were converted, transformed and worked out. Kurt Schwitters’ assemblages were continued into the three-dimensional such that, as in Arman’s garbage accumulations or in the work of Jasper Johns, the things themselves were glued onto the picture, or in reverse, pictures were mounted in the objects and put together into tableaux rich in references and complex in their interrelations. Art inscribes itself in the real, in relation to which it situates itself not only symbolically, but also in occupying a place. In this way it completes the transition from singular object to complex aesthetic reality that is no longer observed, but must be expressly entered and in so doing, thrusts itself itself upon the recipient - as in Edward Kienholz’ environments - and holds up to him the mirror of his own voyeurism. At the same time, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol take up Marcel Duchamp’s Ready made again and arrange it into artifacts of the banal. No longer is art capable of or in a position to outdo the aesthetic of articles of mass consumption; rather, Warhol’s unadorned reproductions like Campbell’s Soup Can (1968) or the Brillo Boxes (1970) are evidence of the utter lack of distinction between the fine art object and the every-day object, and thereby penetrate to the core »of the philosophical question as to the essence of art,« as Arthur Danto put it.

The radicalization of the questioning reaches its height in Beuys’ Expanded Arts. It seeks the emancipation of art from the ghetto of culture, by revealing its autonomy as a phantom that separates it, enclosed in its imaginary world, from society. Instead, Beuys counters the crisis of creativity with the potential of fantasy to become the real impetus behind social development. Thus he becomes a metaphysicist of a universal concept of art: »Everyone is an artist« and »Art is God and the world.« The aesthetic accordingly celebrates its boundlessness. And yet it thereby loses in reverse any and all distinction in respect to its other: with the absolute generalization of art, Beuys decrees its absolute negation. It crosses that threshold beyond which the talk of art itself becomes meaningless, and delivers it up to that narcissistic boundlessness that the representatives of the classical avant-garde reproach the products of the postmodern of.

The negation cuts the continuity of the avant-garde to the quick; for this reason, Beuys, like Warhol, is the central figure of a fundamental change of position in a culture that, with a new self-understanding of art, is already beyond the modern period. Fittingly, Danto speaks therefore of an »art after the end of art.« Something crystalizes out as alternative; it bears only provisory names, and its definition is as yet unclear. The ›post-avant-garde‹ has been spoken of, or - following Achille Bonito Oliva and Jean Baudrillard - ›trans-avant-garde.‹ Yet a tendency to that »performativity« which Lyotard showed to be characteristic of postmodernism is common to all the different projects and projects of the ›post-Warhol‹ and ›post-Beuys' era. A transition from the primacy of meaning and legitimacy to the preeminence of impact and effect is inherent in performativity. The Jungen Wilden whose ›bad paintings‹ are classified as neo-Expressionism, the Italian Arte Cifra or the American New Image Painting can also be accused of this. They do not document a return of pictures, any more than the repetitive music of Steve Reich or Philip Glass documents a renaissance of the tonal, but rather a kind of composing that no longer refers back to any tradition, but proceeds essentially performatively. ›Postmodern‹ means, then, neither plurality nor the absence of criteria, but rather a lifestyle fundamentally transformed, in which art and aesthetic play a different role and group themselves around the categories of ›strength‹ and ›intensity.‹ Therefore it is no longer a question of what art is, but what it releases or triggers, how it intervenes in the practical, in politics, in the concrete patterns of perception of the individual and his structures of consciousness.

In other words, art is becoming essentially ›event‹. Gilles Deleuze names »pre-individuality,« »impersonality« and »incomprehensibility« as its characteristics. This means that no event can be reduced to its individual components, nor can it refer to an external order. Its ontological status is rather that of singularity. It happens as unique, unrepeatable moment and exhausts itself in the moment of its being. Naturally this does not mean that it could not be produced - but its aesthetic production requires precise practices and means of staging and organization. Techniques of symbolisation enter into it, as well as the production of surroundings that necessitate exact calculation and discipline in order to be successful as such. For this reason, Michel Foucault said the event »is [...] definitely not immaterial, because it is always at work on the level of materiality [...]; it has its place and exists in relation to, in coexistence with, in the dispersion of, in the overlapping with, in the accumulation and selection of material elements.« Nevertheless, the event, although ›made,‹ always remains unanticipatable, it kindles its own dynamics that, behind the actors’ backs, always produce something quite different from what they could have imagined.

For this reason, Allan Kaprow oriented the principle of the happening on the accident. All accident happens; it dissolves all familiar ties, confuses the senses and causes one to lose countenance. It is the event of the loss of countenance par excellence. The same is true for the multimedia spectacles of the Wiener Aktionskunst or the feminist Performance. It is in the disconcertedness, the loss of orientation that the real radicality of the aesthetic performances, their scenarios and shock pictures lies. »Radical« literally means ›to-go-to-the-roots.' It is the roots of that existential and bodily ›abandonment, being at the mercy of' [Ausgesetztseins] that strikes one dumb and comes before thought. In enlightened times and demystified reality art after the avant-garde thus approaches again the mystery of the fateful passage. And it reimburses it for that which it lost in the aftermath of its avant-gardistic experiments: its aura. It seems that thus art at the end of its avant-gardistic century returns to a restitution of the cultic that, in the midst of pluralistic plentitude and beyond mere intellectual reflection or aestheticism without consequences, lends it again religious lustre and its original ethical significance.

Dieter Mersch

— MoMo - Berlin

Les appropriations dans l'art

----

«Dans le sens le plus étroit, on parle d'appropriation, si ‹ des artistes copient consciemment et avec une réflexion stratégique › les travaux d'autres artistes. Dans ce cas, l'acte de ‹copier› et son résultat doivent être compris également comme de l'art (sinon, on parle de plagiat ou de faux).

Au sens large, peut être de l'appropriation artistique tout art qui réemploie du matériel esthétique (par ex. photographie publicitaire, photographie de presse, images d'archives, films, vidéos, etc.). Il peut s'agir de copies exactes et fidèles jusque dans le détail, mais des manipulations sont aussi souvent entreprises sur la taille, la couleur, le matériel et le média de l'original.»

Le plus grand bouleversement artistique du XXe siècle est sans doute une des pratiques la plus représentative du phénomène d'appropriation. Il s'agit du ready-made, dont Marcel Duchamp «invente» le principe en 1913 lorsqu'il expose sa Roue de bicyclette, composée d'une roue (sans pneu) fixée par sa fourche sur un tabouret en bois. Ces deux éléments sont issus d'un acte de récupération d'objets manufacturés, et non de création de la part de l'artiste. Le principe de ready-made (choisir un objet manufacturé et le désigner comme œuvre d'art) était donc posé, donnant dès lors naissance à une grande partie des pratiques artistiques et culturelles qui suivirent cette date.

« L'invention du ready-made représente un point de basculement de l'histoire de l'art, dont la postérité est colossale. À partir de ce geste limite, qui consiste à présenter en tant qu'œuvre d'art un objet de consommation courante, c'est tout le champ lexical des arts plastiques qui se trouve ‹ augmenté › de cette nouvelle possibilité : signifier non pas à l'aide d'un signe mais à l'aide de la réalité elle-même.»

Par la suite, Marcel Duchamp récidive en 1914 avec Porte-bouteilles puis surtout en 1917 avec Fontaine. Cette œuvre célèbre, constituée d'un urinoir en porcelaine renversé et signé R.Mutt, et véritablement le premier ready-made destiné à une exposition d'art moderne, médiatisé et controversé (sûrement l'œuvre la plus discutée du XXe siècle).

De fait Fontaine fait donc réellement entrer cette nouvelle technique artistique dans les esprits.

Le ready-made est une démarche conceptuelle d'emprunt, d'appropriation, de recontextualisation. Cette pratique représente sans doute le mieux l'art de l'époque de reproductibilité technique dont parle Benjamin: le ready-made peut être remplacé, reproduit (Fontaine ne survit d'ailleurs qu'à travers ses répliques), multiplié…

«D'essence immatérielle, le ready-made n'a par ailleurs aucune importance physique : détruit, il peut être remplacé, ou pas. Nul n'en est propriétaire.»

C'est également un art du choix, de la sélection et les artistes du ready-made insistent sur cet aspect. André Breton, par exemple, définit le ready-made comme un « objet usuel promu à la dignité d'objet d'art par le simple choix de l'artiste » et Marcel Duchamp insiste : « Quand vous faites un tableau ordinaire, explique-t-il, il y a toujours un choix: vous choisissez vos couleurs, vous choisissez votre toile, vous choisissez le sujet, vous choisissez tout. Il n'y a pas d'art ; c'est un choix, essentiellement. Là , c'est la même chose. C'est un choix d'objet.»

D'une toute autre façon, l'emprunt trouve également une voie d'expression en la personne de Pablo Picasso. Celui-ci n'opérait pas un emprunt direct comme le faisait Duchamp, mais il puisait plutôt sans cesse son inspiration chez ses maîtres et le revendiquait. « Ce type de pratiques trouve en Pablo Picasso une figure idéale, une sorte de fixatif, à tel point qu'il incarne le recyclage. L'admirateur des Ménines de Vélasquez, le génial visiteur d'Ingres ou de Nicolas Poussin a effectivement défini un gabarit pour un usage moderne de l'histoire de l'art.»

En effet, ce dernier, dans ses multiples fractures opérées avec l'académisme et les valeurs établies, n'opère pas un rejet de l'art qui le précède mais noue plutôt un dialogue constant avec lui. Il se nourrit de façon boulimique de ses maîtres et utilise son occupation de grand collectionneur en la réinjectant dans son propre travail sous formes de citations, références, détournements, recontextualisations ou ironie. En témoigne par exemple l'exposition Picasso et les maîtres qui lui fut consacré en 2008-2009 aux Galeries nationales du Grand Palais à Paris.

Durant les années 1950, le groupe des affichistes constitue une autre approche de l'appropriation artistique avec notamment Jacques Villeglé et Raymond Hains. À partir de 1949, ils commencent à récolter dans la rue des affiches déchirées. Celles-ci sont parfois photographiées, mais plus souvent directement exposées, comme telles ou après un travail de recomposition ou recadrage. Ils développent ainsi une approche de la collection, du prélèvement, de la sélection… Pour eux, l'artiste étant alors le « lacérateur anonyme », la figure du collecteur, du collectionneur et du sélecteur prend le pas sur celle de l'artiste qui s'efface.

Tout comme les dadaïstes, ils accordent aussi une grande importance au choix et les sélectionne souvent selon les possibilités de recadrage qu'elles offrent. Pour Villeglé, « le prélèvement est le parallèle du cadrage du photographe ». Se joue alors également dans leurs œuvres un travail sur la mémoire collective fragmentée, les différentes strates des affiches déchirées laissant apparaître les vestiges de certaines plus anciennes.

À la même période, aux États-Unis, certains artistes vont être qualifiés de néo-dadaïstes. C'est le cas notamment de Robert Rauschenberg et Jasper Johns qui travaillent avec des objets de la vie quotidienne qu'ils assemblent et intègrent comme matière à leurs compositions dans une démarche proche de celle du ready-made. On peut penser par exemple à Painted Bronze (1955) de Jasper Johns, constitué de deux canettes de bières. Robert Rauschenberg, lui, développe le principe de Combine Paintings dès 1954. Il s'agit de mêler sculpture, peinture, collages… combinés dans une composition. Ainsi, dans Monogram (1955), il combine une chèvre angora (empaillée) dont la tête est peinte et qui se trouve debout sur une toile horizontale, au sol. L'animal est entouré d'un pneu de voiture et de différents collages (balle de tennis, papiers imprimés, morceaux de bois). Il réalise la même année Bed où il accroche au mur, à la verticale, un matelas recouvert de draps qu'il a badigeonné de peinture.

« Les objets que j'utilise sont la plupart du temps emprisonnés dans leur banalité ordinaire. Aucune recherche de rareté. À New York, il est impossible de marcher dans les rues sans voir un pneu, une boîte, un carton. Je ne fais que les prendre et les rendre à leur monde propre…»

Ces deux artistes américains vont être à l'origine du pop art. Pour ce nouveau courant, «il s'agit principalement de présenter l'art comme un simple produit à consommer : éphémère, jetable, bon marché… […] Il conteste les traditions en affirmant que l'utilisation d'éléments visuels de la culture populaire produits en série est contiguë avec la perspective des beaux-arts lorsqu'il enlève le matériel de son contexte et isole l'objet, ou le combine avec d'autres objets, pour la contemplation. Le concept du pop art se présente plus dans l'attitude donnée à l'œuvre que par l'œuvre elle-même. […] Ce mouvement a perturbé le monde artistique d'autres manières, par exemple à travers la remise en cause du principe d'unicité de l'œuvre d'art.»

En effet, la plupart des artistes de ce courant utilisent directement des éléments tirés du réel dans leurs travaux, et la plupart du temps, ceux-ci proviennent de la culture populaire de masse, et donc sont voués à la reproduction multiple à grande échelle. «L'image reproduite dans son intégralité advient avec le Pop art, par l'appropriation des icônes de la culture de masse et de l'imagerie des médias. La reproductibilité, la multiplicité des couches médiatiques sous lesquelles l'œuvre s'enfonce de plus en plus, annonce l'un des postulats essentiels du postmodernisme : la crise de l'originalité. Cette crise de l'originalité stigmatise la dissolution de l'œuvre originale dans le flux de ses reproductions et de ses médiations technologiques.»

Warhol, figure la plus médiatisée du courant, s'appropriait constamment des objets de la vie courante et des photographies des médias de masse réutilisées dans ses œuvres qu'il reproduisait par dizaines voir par centaines, bouleversant les notions de valeur de l'œuvre par son unicité. L'exemple le plus célèbre est Campbell's Soup Cans, composé de trente-deux toiles sérigraphiées représentant chacune une boîte de conserve de soupe Campbell (une de chaque variété de soupe proposée par la marque), où il s'approprie ainsi cet objet banal de consommation. Il en va de même pour les photographies médiatisées de célébrités qu'il récupère et sérigraphie en grandes quantités. La plus connue, Diptyque Marilyn (1962), contient cinquante images de Marilyn Monroe, toutes basées sur la même photographie publicitaire. À la fin de sa vie, Warhol réalisera également des sérigraphies à partir de reproductions de tableaux célèbres (La Naissance de Venus de Botticelli en 1984 et La Cène de De Vinci en 1986).

Ces démarches sur l'image se trouvent assez proches de celles de Roy Lichtenstein qui peignait dans les années 1960 des images extraites de bandes dessinées populaires. Il est d'ailleurs amusant de remarquer comme le pop art de Warhol ou de Lichtenstein a profité d'un accueil favorable dès sa naissance de par son esthétique lisse et colorée et ses sujets complaisants, par rapport à Dada et les ready-made qui ont toujours été décriés et dont la démarche et l'esthétisme sont plus radicales et brutes.

Dans les années 1960 émerge en France un courant à visée aussi bien politique qu'artistique. Il s'agit de l'Internationale Situationniste, dont les pratiques d'appropriations sont les principaux outils, et plus précisément celle du détournement, dont ils sont d'ailleurs les premiers à employer le terme en art. Dans le premier numéro de sa revue, l'Internationale Situationniste donne cette définition du détournement: «S'emploie par abréviation de la formule : détournement d'éléments esthétiques préfabriqués. Intégration de productions actuelles ou passées des arts dans une construction supérieure du milieu. Dans ce sens il ne peut y avoir de peinture ou de musique situationniste, mais un usage situationniste de ces moyens. Dans un sens plus primitif, le détournement à l'intérieur des sphères culturelles anciennes est une méthode de propagande, qui témoigne de l'usure et de la perte d'importance de ces sphères.»

L'Internationale Situationniste revendique le détournement et le systématise. Ils entendent « piller dans les œuvres du passé » mais « pour aller de l'avant », et envisage cette pratique « comme l'une des méthodes les plus efficaces pour torpiller le ‹ spectacle › et créer une situation nouvelle. Utilisé initialement dans le domaine esthétique surtout, il fut élargi à la production théorique et à l'action politique, jusqu'à devenir la marque distinctive de tout le mouvement.»

En effet, pour Guy Debord, la réappropriation est un moyen de neutraliser l'aliénation du sujet dans la société spectaculaire. Le détournement consiste à faire perdre le sens premier de l'original et lui en donner un nouveau, le recontextualiser. «Les deux lois fondamentales du détournement sont la perte d'importance – allant jusqu'à la déperdition du sens premier – de chaque élément autonome détourné ; et en même temps, l'organisation d'un autre ensemble signifiant, qui confère à chaque élément sa nouvelle portée.»

Dès lors, un lien est tissé entre les objets réunis ou confrontés. Wolman et Debord déclarent à ce sujet que « les découvertes de la poésie moderne sur la structure analogique de l'image démontrent qu'entre deux éléments, d'origines aussi étrangères qu'il est possible, un rapport s'établit toujours.»

On peut par exemple citer les livres d'artistes La Fin de Copenhague (1957) et Mémoires (1959), fruits de la collaboration entre Guy Debord et Asger Jorn, qui sont des livres « entièrement composé d'éléments préfabriqués », où chaque page se lit en tous sens, et où les rapports réciproques des phrases sont toujours inachevés. On trouve également parmi les détournements des situationnistes de nombreuses planches ou cases de bande dessinées, publiées dans leur revue et leurs bulletins et dont ils remplacent les textes des phylactères (la plupart du temps avec des messages politiques).[...]

— Rhizome Sonore