The Disappearance of the Outside

An interview with Andrei Codrescu

by Simeon Alev

Introduction

I first heard of Andrei Codrescu when someone asked me if I had seen Road Scholar, his 1992 documentary, in which the Romanian-born American poet and National Public Radio commentator drives across America in a red Cadillac convertible, stopping at unpredictable destinations to take the spiritual pulse, like a sincere but bemused country doctor, of his adopted homeland. No, I hadn't seen Road Scholar—in fact I had never heard of it—but as a member of a radical spiritual community, the odds were good that when I did, it would be in a communal setting at least superficially similar to some of those Codrescu had visited and filmed. And so it was that one evening last winter, in a makeshift screening room filled to capacity with many of my closest friends, I first made the acquaintance of Andrei Codrescu.

Road Scholar proved delightful and captivating. Codrescu's unique vantage point—expatriate of totalitarian post—Stalinist Romania and astute critic of the totalistic superficiality of modern America—gives the narration its delicious irony. His is a complex sensibility in which cynicism and idealism vie for supremacy and neither (at least in the film) ever conclusively wins. This tension creates a transparency through which those he interacts with are able to reveal themselves completely. Yet at the same time Codrescu is thoroughly and unapologetically opinionated, and his voice-over pronouncements are deadpan but deadly. At one point he says, "I felt that somehow I knew all these folks. They were the friends I lost to gurus in the sixties and seventies, grown a bit older. . . . They made me uneasy. Is there something wrong with the rest of us? . . . Probably—speaking for myself. On the other hand, the oddness of a theocratic hierarchy right in the middle of a representative democracy isn't calculated to make me feel any better." When the show was over and the lights came on, I looked around the room and asked myself, "What would Andrei Codrescu make of us?"

As this issue of What Is Enlightenment? began to take shape, my question acquired intriguing new dimensions. The commercial triumph of popular spirituality in the West was a phenomenon we wanted to examine in the most rigorous context possible, taking as our standard the arduous challenges and awesome potential that characterize the highest spiritual teachings. We hoped to create a forum in which it would be possible to discriminate clearly among the incredible variety of paths and approaches being propagated today in the name of transformative spirituality or enlightenment. And we felt certain that the unique insights of a social critic such as Andrei Codrescu could help us to understand some of the cultural factors which contribute to the epidemic blurring of what we feel are crucially important distinctions. But I wondered . . . did we speak the same language?

"That's right up my alley," Codrescu told me on the phone from his office in the English Department at Louisiana State University, after I had sent him my proposal for an interview. "I wrote a book about this which you might want to read. It's called The Disappearance of the Outside."

The Disappearance of the Outside (subtitled "A Manifesto for Escape") is unlike any of the numerous kaleidoscopic volumes of poetry, memoirs and often hilarious social commentary that Codrescu has also published. It is a profound and intricately reasoned indictment of contemporary Western society, in which the cultural economy of the capitalist West is shown to be as oppressively destructive to the human spirit as were the Orwellian regimes of the Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc under which he grew up. The promise that Western-style democracy appears to hold for Eastern European countries newly open to its influence is deceptive and dangerous, Codrescu asserts, not only to their own citizens but to humanity as a whole. Why? Because the collective consciousness of the West, which threatens now more than ever before to become the dominant consciousness of the world, is unnaturally suffused with images, images designed to disconnect human beings from the uncontainable mystery of what Codrescu calls "the Outside."

"The difficulty of distinguishing between the illusions of commodity culture and reality haunt the art of our time," he writes. "Memory, never very reliable, is easily fooled. The copy cannot be told from the original. When the memory of the 'real' goes, the image may not even bear much resemblance to the original. . . . We will live in an abstract world (if we don't already). The real will have become strictly mythical. We won't notice the disappearance of the Outside, or our lack of desire for it."

Codrescu's analysis helped to explain our frequent bewilderment when confronted with so many popular and presumably convincing approaches to spiritual life that begin to seem dubious the moment they are examined in the context of that rarest but most authentic of attainments, that "pearl of great price," the literal human embodiment of perfect goodness, of that which is truly sacred. His revealing description of America as "an uninterrupted anthology of fads chasing each other faster and faster across shorter and shorter time spans" is recognizably the condition of much of the modern spiritual world, and there is certainly more than enough evidence to suggest that things in general are every bit as bad as Codrescu says they are.

In the course of our conversation, Codrescu readily admitted that growing up in the shadow of a communist dictatorship has left him with the indelible conviction that perfect goodness is neither attainable nor desirable, and that the very aspiration to realize it can only be motivated by a desire to impose on oneself and others a standard of morality and conduct that is suspiciously absolute and almost inevitably oppressive. But at the same time, he derives and transmits a palpable joy from peering with relentless clarity beneath the rampant superficiality of American culture, and his unusual willingness to face reality directly reflects an inspiring commitment both to the discovery of truth and to the preservation of mystery.

Interview

WIE: Road Scholar was our point of entry into your world, and one of the things that struck us as we watched it was that it had quite a strong spiritual emphasis. Was it your intention from the beginning to interview so many spiritual practitioners of one kind or another, or did it just happen that way as the project unfolded?

Andrei Codrescu: No, we certainly planned it that way. There were two things that interested me when I started elaborating the idea of the film. One was, what is the state of communal experiments after the fall of the big communal experiment in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union? Some of the early American utopian communities were used by Marx and Engels to elaborate their theory of communism, and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union took that as far as they did by transforming these utopias, in the process, into something that didn't resemble the original versions at all. But some of these communities are still here, and I wanted to know why. And the other thought I had was that I wanted to revisit some of my past. In the past—the late sixties to mid-seventies—I knew quite a few people who were interested in spiritual life and I was close enough to them to witness and occasionally to participate.

WIE: How do you see the state of spiritual life in America today?

AC: I feel that the sixties were the fountainhead of everything bad and good in America today, but as far as the proliferation of various kinds of techniques for attaining enlightenment, I think that that has been largely a function of the market. The great discovery of the early seventies was that the great new markets are interior—they're inward, they're spiritual—and that that was the direction that we were going to go in because we had pretty much exhausted physical space in America. And entrepreneurs of the spirit, if you like, took the cue from there.

WIE: Santa Fe comes across in the film as the quintessential New Age Mecca.

AC: Yes, Santa Fe is clearly the film's locus of what's being marketed, and if you've read the book you know that I met many more people there than were shown in the movie. I found most of them to be charming frauds. Just about everybody seemed to be operating on the surface level of suggestion and gimmickry—crystals, aura healing, etcetera. And then there were the out-and-out psychotics. . . .

WIE: Why do you think that this country has been unable to sustain the kind of radical self-inquiry that was embraced in the sixties? In the nineties, spiritual interest seems to be no less widespread but it doesn't seem to be propelled by the same degree of selfless passion and willingness to risk everything. You were nineteen when you came here in 1966. What is your former nineteen-year-old émigré's perspective on what happened in the sixties and what's happened since?

AC: The sixties was one of those epochs like the twenties—the twenties into the thirties—that suddenly compelled everyone to an urgency that was quite miraculous. These sorts of evolutionary periods occur, but I can't claim to understand why they happen. All I know is that there are tremendous energies loose in the collective body that are competing, and in the twenties and thirties, most of the important thinking in philosophy, in psychology, in ethnography, in history, in geology, was being done. You had, in France, the surrealist writers, Jacques Lacan in psychology . . . quite a few people working in various areas. And what they were competing with at that time was fascism, which was an extremely strong and simplified recipe for suicide. So you could say that this tremendous explosion of creative activity was a rush to find out what human beings were before they were going to be killed. I think that in the sixties we had the same feeling. It was another end of history—there have been several ends of history that have occurred since Nietszche proclaimed the death of God—and we experienced the same kind of urgency. We wanted to put human life on a new basis. We wanted to find out whether it was possible to live without war, to live in a different way. And that impulse translated itself into an emergency, a psychic emergency. But a very strong wave of oppression soon followed the optimistic explosion of the sixties, and what happened as a result was the translation of the spiritual quest into the realm of politics. Because while of course the FBI and the other oppressive institutions of the government couldn't understand the spiritual quest, they did understand politics, and once things were translated into politics it became easier for them to suppress it.

So for a while America had been nineteen years old just like I was, but now it began to age very quickly. This was partly because the war had disappeared, so there was a different status quo, and partly because we were suddenly introduced to several alternative realities, really that started with Ronald Reagan, who was an absolutely brilliant hologram, a projection of several authoritarian desires in the body politic. What he presented us with was a renewed sense of nationalism, the promise of a shining economy in which everybody could participate so that they could have whatever they wanted, not by trying to change the way they lived but simply by buying it. That was really the beginning of the triumph of consumer society in a very, very big way. And as people got older, pretty soon they began to worry about making a living and then the urgency left. A more radical way to think of it is that the last train for God left America in about 1974. There was a great rush to get on board and many people did—they either died or were marginalized to some place where they still exist. But the rest of us stayed behind and tried to organize life as best we could.

WIE: Georg Feuerstein, elsewhere in this issue, distinguishes between authentic liberation teachings and "watered-down versions of powerful original teachings made palatable to Western consumers." What aspects of our culture would predispose spiritual seekers to accept these diluted teachings? And what is it that has to be removed from genuine teachings in order to make them attractive to Americans?

AC: Our consumer culture is both material and spiritual, and the success of consumerism and spectacle has to do with packaging. You could say that more than two-thirds of the things that make us happy do so because of the package they come in, the box. There's nothing inside. Our attention span has been severely reduced over the past two or three decades. Some people blame television, and it's probably true. But Attention Deficit Disorder is not an entirely negative condition. We also have ADD, or a reduced attention span, because we want to absorb and incorporate more and more information and more and more products in order to make sense of our world. It is only an ascetic minority that tries to do without things, without technologies, without consumption, but even they are inextricably linked to these things. Even those people who consciously refuse to participate are still connected to the global culture, so in a sense there is no choice but to be within it and to think it. So our short attention span comes from an effort to defend our humanity and also our sense of self from a culture that splits it all the time, that divides it, divides it, divides it. Because capitalism is schizophrenia; it is a multiple-personality-producing force. In order to defend yourself against that you have to absorb very fast more and more, and so you don't pay enough attention.

But there is another aspect to your question about making a spiritual package that is pleasing or saleable. Historically, as we all know, true shamans and spiritual people have been shunned by most communities. They have been ostracized. The shamans had to live in a tree and they were dirty and frightful people, and when they came to the edge of the village, it was only the fact that they had spiritual and healing powers that kept the people from beating them with sticks and destroying them. And it seems to me that the shaman's perspective is the one from which to question the genuineness of any spiritual package that doesn't transform you into a complete freak who has to eat worms and live in the desert, that allows you to still live in your community and not be an outcast. Because a palatable spiritual package, to me, runs the danger of not having enough energy or of not being spiritual enough—an effect of being pretty much just a dilettante's dabbling in superstition. I really think that the genuinely spiritual person is dangerous, and charged with a kind of frightful energy and antisocial power. And when they appear, they will be shunned.

WIE: How do you feel, then, about people who are trying to make spiritual teachings popular by "defanging," to use your words, or "denaturing" them by removing the offensive or subversive elements you've touched on so that people will become interested in them?

AC: Those people are dangerous, actually. They're dangerous because they present a virtual reality in lieu of reality. Anybody who gives you a wax apple and tells you it's a real one, you know, you'll figure it out when you take your first bite. But for a while there, after you've bothered keeping it and you're not really eating it, they think you won't know the difference. And a lot of people don't.

The greatest enemy of the real is the seemingly real. And that is something we've gotten very good at doing—faking reality, faking the objects of our interest, presenting substitutes. This is a culture of simulation. It is possible for a poor person to think they are living as well as a rich person because what they buy looks the same, but theirs is made out of cheap s— while the rich people buy the stuff that's made out of genuine material.[...]

— The Magazine for Evolutionaries

Andrei Codrescu

Andrei Codrescu is a Romanian-born American novelist, poet, editor, and radio commentator. Noted for his command of everyday American English in his writings, Codrescu writes spare, forthright poetry noted for its exacting language and imagery and playful, irreverent wit. His poetry, which reveals the influences of the Dadaist and Surrealist movements, has been likened to the works of Walt Whitman and William Carlos Williams for its replication of American vernacular.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Youth in Communist Romania Born Andrei Ivanovitch Perlmutter on December 20, 1946, in Sibiu, Romania, Codrescu was raised in the turbulent political atmosphere that followed World War II. By the end of the war, Romania was fighting with the Allies against Germany, but because it was under the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union, it became a Communist country led by Premier Petru Groza. As part of the Soviet-Influenced Eastern bloc, Romania was Communist and followed a pro-Soviet agenda. Codrescu began writing poetry at the age of sixteen and continued to do so while attending the University of Bucharest, where he changed his named to Codrescu. He became involved with his country’s literary intelligentsia prior to publishing several poems critical of Romania’s Communist government.

Escape to the West expelled from the University of Bucharest for his criticism of the Communist government, Codrescu fled his homeland before being conscripted into the army. Traveling to Rome, the young writer learned to speak fluent Italian and earned his master’s degree from the University of Rome. He then went to Paris and finally to the United States with his mother. Arriving in America in 1966 without any money or knowledge of English, Codrescu was nonetheless impressed with the social revolution that was occurring around the country as Americans changed how they looked at themselves, each other, and the world. At this time, there was a strong call for increased individual rights, including the civil rights movement, which sought to increase equitable treatment for African Americans and a burgeoning feminist movement that wanted rights for women. There was also a powerful antiwar movement protesting American involvement in the on-going Vietnam War.

Poetry influenced by Life in America As Village Voice contributor M. G. Stephens relates, Codrescu quickly ‘‘hooked up with John Sinclair’s Artist Workshop. Within four years he learned to speak American English colorfully and fluently enough to write and publish his first poetry collection, License to Carry a Gun (1970). The collection was hailed by many critics who recognized Codrescu as a promising young poet.

Codrescu then published his acclaimed second collection of poetry The History of the Growth of Heaven (1971), and followed it with two books of autobiographical prose, The Life and Times of an Involuntary Genius (1975) and In America’s Shoes (1983). In the early 1980s, Codrescu was also influential in that he founded the literary journal Exquisite Corpse and became a weekly commentator on All Things Considered, a popular show on National Public Radio. The same year, he published a collection of his broadcast essays Craving for Swan (1986), he published Comrade Past and Mister Present, a highly regarded collection of prose, poetry, and journal entries.

Return to Romania Codrescu returned to Romania after twenty-five years to observe firsthand the 1989 revolution, which shook dictator Nicolai Ceausescu from power. Ceausescu had gained power in the early 1960s, and while a Communist, moved the country away from Soviet influence over the next few decades. However, the dictator ruled his country with an iron fist and was not open to reform. A popular uprising removed Ceausescu from power with the help of Romania’s army, and he and his family were executed. The range of emotions Codrescu experienced during this time, from exhilaration to cynicism, are described in the volume The Hole in the Flag: A Romanian Exile’s Story of Return and Revolution (1991).

Initially enthusiastic over the prospects of a new political system to replace Ceausescu’s repressive police state, Codrescu became disheartened as neo-Communists, led by Ion Iliescu, co-opted the revolution in the early 1990s. Though he agreed to ban the Communist Party and institute reform, Iliescu himself exhorted gangs of miners to beat student activists ‘‘who represented to Codrescu the most authentic part of the revolution in Bucharest,’’ according to Alfred Stepan in the Times Literary Supplement. ‘‘It seemed to him the whole revolution had been a fake, a film scripted by the Romanian Communists.’’ As Codrescu wrote of his impression and opinions of his mother country in the book, Romania remained unstable, marred by civil unrest and corruption, and economically impoverished for at least the next decade.

Continued literary career in the United States In preparation for his 1993 book and documentary film Road Scholar: Coast to Coast Late in the Century, Codrescu drove across the United States in a red Cadillac accompanied by photographer David Graham and a video crew. Encountering various aspects of the American persona in such cities as Detroit and Las Vegas, Codrescu filtered his experiences through a distinctively wry point of view. ‘‘Codrescu is the sort of writer who feels obliged to satirize and interplay with reality and not just catalogue impressions,’’ observed Francis X. Clines in the New York Times Book Review, who compared Codrescu’s journey with the inspired traveling of 1950s ‘‘road novelist’’ Jack Kerouac.

While Codrescu continued to publish poetry volumes such as Alien Candor: Selected Poems, 1970–1995 (1996) and It Was Today—New Poems by Andrei Codrescu (2003) as well as several collections of essays, including The Muse Is Always Half-Dressed in New Orleans (1995), the author branched out into other literary genres. He published his first novel in 1995, the Gothic thriller The Blood Countess, and a collection of short stories in 1999, A Bar in Brooklyn: Novellas and Stories, 1970–1978.

The novel drew on both his Eastern European background as well as his life in the United States. The title of The Blood Countess refers to Elizabeth Bathory, a sixteenth-century Hungarian noblewoman notorious for bathing in the blood of countless murdered girls. Codrescu tells Bathory’s gruesome story alongside a contemporary narrative about the countess’s descendant, Drake Bathory-Kereshtur, a U. S. reporter of royal lineage working in Budapest who meets up with various manifestations of Elizabeth before he is seduced by her spirit to commit murder.

An English professor at Louisiana State University, Codrescu also continues to contribute to National Public Radio program All Things Considered.

Works in Literary Context

Codrescu writes spare, forthright poetry noted for its exacting language and imagery and playful, irreverent wit. His subject matter is largely autobiographical, often consisting of recollections of his youth in Communist Romania and his experiences as an expatriate living in Rome, Paris, and the United States. Codrescu eschews controversy in favor of a mock-revolutionary pose and a disillusioned yet resistant attitude. He is frequently commended for perceptive insights into American culture as viewed from a foreigner’s perspective.

Oppression although Codrescu enjoys the freedoms that exist in the United States, he is still as critical of bureaucracy in his adopted country as he was in his native Romania—a skepticism that is made evident in his poetry and his autobiographies, The Life and Times of an Involuntary Genius and In America’s Shoes. The author uses his poetry and essays to focus on the idea of oppression, something which he fearlessly confronts.

Cultural differences just as Comrade Past and Mister Present compares East and West through poetry, in The Disappearance of the Outside: A Manifesto for Escape Codrescu discusses the matter in direct prose. He addresses such subjects as the mind-numbing effects of television and mass marketing, the sexual and political implications that are a part of language, and the use of drugs and alcohol in contrasting life in both parts of the world.[...]

— Literature Essays

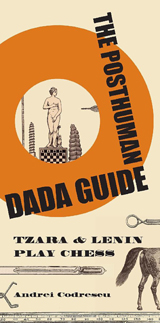

Unique Andrei Codrescu book

One of the more curious items to come to light during the unpacking of the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library was a volume of poems in Italian called L’alito eterna by the obscure Italian poet Renata Pescanti Botta. What made this book so intriguing was that the margins and empty space in the first half were filled with hand-written verse and illustrations in Romanian and the cover bore the manuscript title Femeia neagră a unui culcuş de hoți. The only clue to its authorship was the hand-written name “Andrei Codrescu” on the cover.

The book sat on a shelf for a few years until I came across it in 2006 and decided to investigate this puzzling item. The first step was to work out what I had. I guessed that the manuscript poems were by the Romanian-American poet Andrei Codrescu, well known for his commentaries and reporting for National Public Radio, but I wondered whether his verse was merely a translation of the Italian or original work. Thankfully a faculty member at Emory is fluent in both Romanian and Italian so I took the work to Dalia Judovitz, National Endowment of the Humanities Professor of French and Comparative Literature, who was able to tell me that the poems were original work and were, in fact, amusing riffs on the original Italian poems.

With this knowledge I decided to contact Codrescu directly. He is MacCurdy Distinguished Professor of English at Louisiana State University so his email was easy to find from the university’s website. He replied to my email almost instantly and was very excited to discover this relic from his past though he had only a vague recollection of it. I sent a photocopy to him and his memories returned. He left Romania at age 19 in 1965, traveling via Rome to arrive in the United States in 1966. This book was one that he acquired during his stay in Italy and brought with him to the United States. The poems were written during this period and, as such, are some of his earliest works. He had kept copies of some of the poems but many were unknown.

Copies of the photocopy I had supplied to Codrescu eventually travelled to his editor in Romania where there was great excitement over the discovery of such early work by a well-known Romanian writer. The manuscript poems were transcribed and publication was planned. When the editor saw the colorful illustrations that the youthful Codrescu added to the text then a full digital scan of the work was sent to Romania to be published in addition to the transcribed poems. The end result was the publication of the work in October 2007 by Editura Vinea of Bucharest in a handsome volume with a foreword by the prominent Romanian poet Ruxandra Cesereanu.

This was certainly one of my most satisying discoveries. I would never have guessed when I pulled the book off the shelf that it would lead to a copy of it being published in Romania.

David Faulds

— Emory Libraries

— Andrei Codrescu, Author

— Andrei Codrescu

— Exquisite Corpse

— Mineshaft Magazine´s Website