Jack Kerouac : Hors textes

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) est un des plus grands poètes et écrivains américains des années 50 et 60. Il est le précurseur de ce que l'on a appelé la «prose spontanée». Il écrit son œuvre majeure en 1947, Sur la route et mettra plus de six ans à trouver un éditeur qui veuille bien le publier.

L'œuvre de Jack Kerouac ne peut être comprise dans son ensemble sans les notions de «paratexte» ou encore d'«épitexte» qui la constituent.

Le «paratexte» est formé par un ensemble de notions très vastes qui concernent tout ce qui peut entourer un texte, de ce qui se trouve tout autour de lui. A la fois ce qu'a ajouté l'auteur lui-même et ce que l'on peut ajouter à la compréhension d'une oeuvre en dehors d'elle. Il s'agit principalement de ce que l'on peut appeler le Hors texte(s).

Dans sa définition propre, l'«épitexte» concerne tout particulièrement ce qui ne se trouve pas dans le texte lui-même, mais qui se déploie autour de lui (ou d'une œuvre entière): les entrevues, les couvertures de livres, les correspondances, mais également, selon notre point de vue, la vie de l'auteur. Quel est l'impact du paratexte sur l'œuvre de Jack Kerouac? Quels en sont les Sens Hors textes? Quelles sont la valeur et la finalité d'une telle analyse? Autant de questions sur un rayonnement de l'au-delà du texte auxquelles il faudra répondre au travers de quelques exemples significatifs.

Paratexte et projet d'écriture

Le «paratexte» est souvent considéré à tort comme le «parasite» qui court-circuiterait la compréhension d'un texte. Ne dit-on pas très souvent aux élèves faisant une étude de texte: «le texte, que le texte et rien que le texte»? Il existe une tradition implicite, dans l'enseignement des matières littéraires, qui néglige la vie personnelle et le parcours des auteurs, des philosophes, donnant une place parfois trop importante aux idées développées dans le texte plutôt qu'à ce qui l'entoure. Mises à part les quelques évocations furtives (les dates de vie et de mort de l'auteur, son lieu de naissance, le lieu où il effectue ses études etc.), le contexte historique, la vie et le caractère de l'auteur sont très rarement évoqués. Or, il est indéniable qu'un individu, quel qu'il soit, lorsqu'il entreprend un projet d'écriture (littéraire ou philosophique), ne peut se départir de lui-même, de sa propre vie, de ce qui le constitue, de sa propre expérience. N'y a-t-il pas dans le mot projet la notion de ce qui est projeté. En effet, l'auteur se projette tout entier dans son œuvre avec son histoire et l'histoire de son temps.

Ce qui entoure l'œuvre de Jack Kerouac, au sein même de la notion de paratexte (et plus précisément dans l'épitexte), c'est tout d'abord le rattachement systématique de l'écrivain au mouvement, à la fois connu et méconnu, de la Beat Generation. Ce mouvement est connu par son appellation et méconnu dans son véritable sens.

Le sens Hors des textes

Afin de mieux comprendre ce qui entoure l'œuvre de Jack Kerouac, il est important de s'attacher à ce qui fait Sens Hors des textes de cet écrivain de la Route. Le sens exact des termes «Beat Generation», nous le trouvons non pas dans les romans de Kerouac, mais dans un article du New York Times en novembre 1952 publié par un journaliste-écrivain et critique littéraire, John Clellon Holmes.

Au cours d'une discussion avec Jack Kerouac, John C. Holmes prête attention à une expression de l'auteur censée définir le style de vie des jeunes écrivains dont il fait partie avec d'autres comme Allen Ginsberg ou William Burroughs.

Loin de vouloir signifier «génération perdue», «battue» ou «cassée» comme cela a été dit par les critiques littéraires de l'époque, Kerouac explique, étant d'origine canadienne-bretonne, que le mot «Beat» veut dire «béate».

La simple interprétation malheureuse et pessimiste du mouvement auquel le monde littéraire rattache Kerouac, peut changer la façon d'aborder certains ouvrages tels que Sur la route, Les clochards célestes ou encore Les anges vagabonds. En effet, lorsqu'on s'attarde sur cette littérature du Grand Voyage, loin d'être pessimistes, ces itinéraires de vies sont de véritables plaidoyers à la béatitude et à la poésie.

Le mot «Beat», auquel l'expression fait appel, est également le rythme que Kerouac attribue au jazz et aux battements de cœur qui accompagnent cette musique enivrante : «It's a Be-At, le beat à garder, le beat du cœur». En d'autres termes «C'est un Être à, le tempo à garder, le battement du cœur». Ce Be-At, cette «béatitude» est celle de Charley Parker qui disait «Tout va bien» lorsqu'il jouait.

Observateur privilégié de cette époque hallucinée, Alain Dister décrit cet élan de béatitude. Son témoignage s'intègre au paratexte:

«(Kerouac) se laisse prendre aux cliquetis de la machine comme un razzmatazz de batterie, (il) s'accorde au beat de la frappe, en rythme avec un jazz intérieur – la grande musique des mots, le swing des syllabes, le jazz des phrases – le beat, la pulsion même du roman»

Ce que l'on retrouve dans et hors des textes de Kerouac, c'est cette obsession du rythme, mais aussi cette union si particulière entre l'Être, la musique et l'écriture. Si on ne connaît pas les éléments biographiques concernant Kerouac, il est très difficile de comprendre, «de prendre avec soi», la notion musicale qui se cache derrière chacun de ses textes.

Valeur ontologique

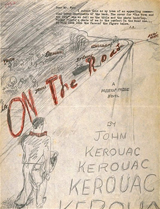

Ainsi, voulant imiter cette musique (le jazz) et son rythme, Kerouac s'emploie à écrire d'une traite, sur un rouleau de trente-six mètres de long, son roman le plus célèbre Sur la route. Il s'agit là d'une rupture stylistique avec un certain académisme, structuré, maintes fois corrigé, exigé par les critiques littéraires et les maisons d'éditions, car cette manière d'écrire privilégie la spontanéité intégrant une pulsion de vie, tel un battement de cœur, une respiration, un rythme musical aux phrases qui se succèdent.

A la lecture de ces œuvres si particulières, il paraît évident que pour sa bonne compréhension, les notions de paratexte et d'épitexte ont une valeur proprement ontologique. Dans l'œuvre de Kerouac, l'auteur célèbre «l'être en tant qu'être» puisqu'il attribue à la musique (au jazz) cette capacité à révéler l'Être : c'est véritablement le battement de l'Être dans le battement de la musique ; c'est ce qu'il appelle le It , c'est-à-dire le «Ça», là où l'Être et le jazz ne font plus qu'Un. Comme en témoigne ce passage que Jack Kerouac consacre à un saxophoniste rencontré dans un club de jazz:

«(...) il a soufflé comme un dément ce soir-là; un copain arrivant du boulot est entré dans la salle à fond de train en criant: «Souffle ! Souffle ! Souffle!» (...) «Attends, Jack, écoute-moi bien, maintenant je vais te dire toute la vérité et rien que la vérité – écoute-le, lui. C'est ça ! Il a le Ça ! Ça ! Ça ! - voilà ce que je voulais t'expliquer tout à l'heure, tu vois, ça et tout le reste. Oui!» (...) et puis ces cris lorsque tout le monde, tous les batteurs, les crâneurs et les rouspéteurs, les cascadeurs des cordes métalliques, (...) tous comprennent que Ça y est, et Ça vient, Ça est là (...)»

C'est le battement de cœur, la pulsion de vie qui se manifeste dans son œuvre.

Il est question d'un discours de l'Être Kerouac, mais également, et au-delà de toute ontologie, d'une naissance de l'Être Kerouac. Entre les lignes, et à la lecture des nombreuses biographies le concernant, nous découvrons à quel point sa vie (faite de traversées des États Unis, de rencontres multiples) et le jazz constituent l'entièreté de son œuvre au-delà des textes eux-mêmes.

L'absence

Les interviews écrites ou télévisuelles que Jack Kerouac a faites, et plus particulièrement les couvertures de ses romans, démontrent à la fois le voyage et la solitude. Mais cette notion musicale si importante dans l'œuvre et la vie de Kerouac y est tragiquement absente, ou évoquée en filigrane, en ombre.

Faut-il penser que le contexte politique de l'époque, le Maccartisme, et une Amérique très puritaine ont eu raison de la dimension musicale dans l'œuvre de Kerouac? Selon cette Amérique conservatrice, le jazz faisait l'apologie de la consommation de drogues, invitait la jeunesse à la «dépravation». Y a-t-il «trahison» du message principal de l'auteur? Trahison, peut-être pas, mais une omission désirée par les éditeurs sans aucun doute. La dimension marketing qui donne à l'ouvrage les perspectives de voyages tant convoitées par la personne humaine et le futur lecteur est privilégiée par rapport à la dimension musicale susceptible de heurter une clientèle conservatrice. Sur la route fut un succès commercial largement boudé par les critiques. Vendu comme un produit, l'Être Kerouac rejette la «Beat Generation» et entame une dépression dont il se remettra difficilement.

Tous ces éléments font partie des «éléments paratextuels» se trouvant annexés aux textes et qui entourent, non seulement l'œuvre de Kerouac.

Textes et Origine

Au travers de la notion de paratexte qu'exprime Gérard Genette, il est important de comprendre l'Idée d'origine d'une œuvre.

Ce concept d'origine dans le paratexte participe de ce lien indiscutable qu'il y a entre l'homme et son œuvre. Cette «humanité» est très souvent oubliée dans la lecture et l'étude de texte sans doute parce que nous sommes issus d'une tradition qui privilégie l'écrit plutôt que l'oral. Cette froideur de l'écrit empêche parfois l'éclosion de l'être qui se cache derrière son œuvre.

Même si le paratexte est essentiel à la compréhension d'une œuvre, d'un ouvrage, d'un auteur, il est important de préciser que cette notion détient une part de subjectivité. Toute personne est en droit d'interpréter à sa manière certains événements, certaines interviews, certains faits. En revanche, il est indéniable que ce Hors textes donne très certainement une dimension tentaculaire, une seconde vie au texte lui-même. Il serait regrettable de ne s'attarder que sur les phrases qui le constituent en oubliant que parfois c'est ce qui est caché, invisible ou méconnu qui en donne toute l'importance. Nous pouvons parler d'une véritable archéologie littéraire c'est-à-dire d'une recherche, d'un discours sur l'origine d'une œuvre. Nous parlons d'archéologie car ce terme soulève à la fois une recherche historique et une quête de Sens. Ce Sens, cette direction, ce chemin vital que cherche avidement l'auteur, mais aussi tous ses lecteurs.

Loin d'être en dehors de tout contexte, l'œuvre de Kerouac est certes un ensemble de textes, mais elle est d'abord et avant tout «née de...». Le texte, au travers du paratexte est une naissance ayant une origine et une fin.

— Loxias

Books of the Times

"On the Road" is the second novel by Jack Kerouac, and its publication is a historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion (multiplied a millionfold by the speed and pound of communications).

This book requires exegesis and a detailing of background. It is possible that it will be condescended to by, or make uneasy, the neo-academicians and the "official" avant-garde critics, and that it will be dealt with superficially elsewhere as merely "absorbing" or "intriguing" or "picaresque" or any of a dozen convenient banalities, not excluding "off beat." But the fact is that "On the Road" is the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by the generation Kerouac himself named years ago as "beat," and whose principal avatar he is.

Just as, more than any other novel of the Twenties, "the Sun Also Rises" came to be regarded as the testament of the "Lost Generation", so it seems certain that "On the Road" will come to be known as that of the "Beat Generation." There is, otherwise, no similarity between the two: technically and philosophically, Hemingway and Kerouac are, at the very least, a depression and a world war apart.

The 'Beat' Bear Stigmata

Much has been made of the phenomenon that a good deal of the writing, the poetry and the painting of this generation (to say nothing of its deep interest in modern jazz) has emerged in the so-called "San Francisco Renaissance", which, while true, is irrelevant. It cannot be localized. (Many of the San Francisco group, a highly mobile lot in any case, are no longer resident in that benign city, or only intermittently.) The "Beat Generation" and its artists display readily recognizable stigmata.

Outwardly, these may be summed up as the frenzied pursuit of every possible sensory impression, an extreme exacerbation of the nerves, a constant outraging of the body. (One gets "kicks"; one "digs" everything whether it be drink, drugs, sexual promiscuity, driving at high speeds or absorbing Zen Buddhism.)

Inwardly, these excesses are made to serve a spiritual purpose, the purpose of an affirmation still unfocused, still to be defined, unsystematic. It is markedly distinct from the protest of the "Lost Generation" or the political protest of the "Depression Generation".

The "Beat Generation" was born disillusioned; it takes for granted the imminence of war, the barrenness of politics and the hostility of the rest of society. It is not even impressed by (although it never pretends to scorn) material well-being (as distinguished from materialism). It does not know what refuge it is seeking, but it is seeking.

As John Aldridge has put it in his critical work, "After the Lost Generation," there were four choices open to the post-war writer: novelistic journalism or journalistic novel-writing; what little subject- matter that had not been fully exploited already (homosexuality, racial conflict), pure technique (for lack of something to say), or the course I feel Kerouac has taken--assertion "of the need for belief even though it is upon a background in which belief is impossible and in which the symbols are lacking for a genuine affirmation in genuine terms."

Five years ago, in the Sunday magazine of this newspaper, a young novelist, Clellon Holmes, the author of a book called "Go," and a friend of Kerouac's, attempted to define the generation Kerouac had labeled. In doing so, he carried Aldridge's premise further. He said, among many other pertinent things, that to his kind "the absence of personal and social values * * * is not a revelation shaking the ground beneath them, but a problem demanding a day-to-day solution. How to live seems to them much more crucial than why." He added that the difference between the "Lost" and the "Beat" may lie in the latter's "will to believe even in the face of an inability to do so in conventional terms"; that they exhibited "on every side and in a bewildering number of facets a perfect craving to believe".

Those Who Burn, Burn, Burn

That is the meaning of "On the Road". What does its narrator, Sal Paradise, say? "* * * The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles. * * *"

And what does Dean Moriarity, Sal's American hero-saint say? "And of course no one can tell us that there is no God. We've passed through all forms. * * * Everything is fine, God exists, we know time. * * * God exists without qualms. As we roll along this way I am positive beyond doubt that everything will be taken care of for us--that even you, as you drive, fearful of the wheel * * * the thing will go along of itself and you won't go off the road and I can sleep."

This search for affirmation takes Sal on the road to Denver and San Francisco; Los Angeles and Texas and Mexico; sometimes with Dean, sometimes without; sometimes in the company of other beat individuals whose tics vary, but whose search is very much the same (not infrequently ending in death or derangement; the search for belief is very likely the most violent known to man).

There are sections of "On the Road" in which the writing is of a beauty almost breathtaking. There is a description of a cross-country automobile ride fully the equal, for example, of the train ride told by Thomas Wolfe in "Of Time and the River." There are details of a trip to Mexico (and an interlude in a Mexican bordello) that are by turns, awesome, tender and funny. And, finally, there is some writing on jazz that has never been equaled in American fiction, either for insight, style or technical virtuosity. "On the Road" is a major novel.

— Dharma beat

Some of the DHARMA

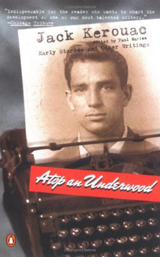

For Jack Kerouac fans and enthusiasts the publication of Some of the Dharma is a major event. This book that had been often rumored and mentioned is now a reality. We can finally hold it in our hands and read the words Kerouac wrote more than 40 years ago after his meditations in the Carolina woods, in Mexico City, Berkeley, San Francisco, Richmond Hill, Long Island and under the Brooklyn Bridge. It brings to mind Kerouac’s line in his fantasy "The Early History of Bop," --- "You can’t believe that bop is here to stay . . . that it is real." Some of the Dharma is here, it’s real, with a picture of handsome young Jack in coveralls on the cover, standing straight to tell it like it is. Empty and awake, a brakeman on the universal freight.

It should be said right off that this book about large Truths and about the annihilation of the discriminating, duality-making ego-self is not nearly as fast or enjoyable a read as Kerouac’s "true story novels" about himself and other discriminating ego-selves. "The Dharma Bums" and "Desolation Angels", for instance, present many of the same Buddhist concepts as Some of the Dharma but they also have story and characters to keep the reader interested. Relying on Buddhist musings alone, Some of the Dharma requires a reader to be in a more meditative frame of mind. There is no plot, no story, no "mad to burn" characters, but there is much of the same wonderful word magic found in all of Kerouac’s work. Interspersed with dharma talk there are many poems and other gems of Kerouacian wordplay. And there is a goal to all of Jack’s meditation and discourse: "From out of this you emerge with loving-kindness, compassion, gladness and equanimity."

There are many ways to approach this somewhat daunting book and each reader will likely adopt his or her own strategy. Some will decide to delve here and there at random. Others may give it a cursory read and come back later for more depth. And some may want to read it in conjunction with the letters of the same period, 1953-1956, or the other Kerouac books that it most closely relates to --- "Visions of Gerard", "Mexico City Blues", "Scripture of the Golden Eternity", "The Dharma Bums", "Desolation Angels", "Book of Dreams", "Pomes All Sizes". I approached it as a kind of meditation, to be taken slowly, in small doses, savored and contemplated.

"Every now and then in the gloom of daily living and daily complaining and daily unhappy horror I get a twinge of joy remembering the original Dharma of Pure brightness, an ancient ecstasy is hiding in the my-mind-middle-Room-Poorhead."

The Kerouac we encounter here is mostly the earnest childlike Buddhist, like Ray Smith in "The Dharma Bums", who wants to "save all sentient beings from suffering and to bring them to eternal happiness." More than any other Kerouac book this one seems apart from his everyday self of storytelling and literary ambition. It is Kerouac’s meditation self that is put on the page here. This book started in December 1953 as notes on Buddhism to Allen Ginsberg. After promising to send Allen the 100-page manuscript, Jack wrote: "I haven’t sent you the Notes on the Dharma because I keep reading it myself, have but one copy, valuable, sacred to me . . . --- Besides it is not finished, I keep adding every day. . . " Indeed there are several times in this book where Kerouac writes as if he is done with it, only to pick it up again not long after. It’s almost like he was not doing it himself, was simply transcribing transmissions received during meditation and study.

Of course there’s a certain paradox inherent in this "wisdom" book by Kerouac, a man who drank himself to an early death. It becomes a "do as I say not as I do" kind of teaching, but that does not negate its validity or negate the poignant fact that during the three-year period of his life while he was writing Some of the Dharma, Kerouac was practicing Buddhist dhyana (meditation) and achieving some happiness and peace of mind. Again the idea of "transmission" suggests itself. For three years Kerouac was picking up Buddhist wisdom on an open channel; then it stopped. By 1959, as he wrote to Philip Whalen: "Myself, the dharma is slipping away from my consciousness and I can’t think of anything to say about it anymore."

"I’m not as big a fool as I used to be, I’m a smaller fool----"

"Reality isn’t bleak nor can it be said to be non-bleak either . . ."

"MY OWN PROVERB: Vest made for flea will not fit elephant . . ."

Kerouac’s dharma talk can be confusing-sometimes sayings, aphorisms, advice; sometimes the multi-faceted Indian Hindu trappings of Mahayana Buddhism; sometimes the liberating, confuse-the-rational-mind quality of zen koans. From out of this jumble certain themes do emerge. One recurring theme is that all sounds are part of "the One Transcendental Unbroken Sound." The corollary to this is that all objects and activities are "d.f.o.t.s.t."---different forms of the same thing (or sometimes "different forms of the same holy emptiness.") Frequently all phenomena are seen as "visionary flowers in the air" or "a dream that has already ended." A dominant theme is taken from the Diamond Sutra: "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form" or "everything is empty and awake." At one point Kerouac writes: "ROCKY MOUNT NEGRO SHACKTOWN, Stopped, wrote this on lamp pole:-’Everything’s Alright--form is emptiness & emptiness is form--& we’re here forever--in one form or another--which is empty’." Imagine the down home folks of 1956 Rocky Mount, North Carolina trying to make heads or tails of that! These several themes and motifs all recur, overlap and interplay kaleidoscopically as Kerouac explores Buddhism in relation to his everyday life. It goes on and on and on and on. (Did you think Some of the Dharma would be some quick little light read? Think again, oh dweller in illusion.)

Another way to look at this book, and Kerouac’s Buddhism, is as an attempt to find a way to keep from drinking himself to death. He writes: "I don’t want to be a drunken hero of the generation suffering everywhere with everyone. I want to be a quiet saint living in a shack in solitary meditation of universal mind." But we know what happened. Jack keeps making his desert hut plans-retreat, plain food, no drinking. It’s a sad effort, touching, triste. But the paradox of his alcoholism is also present here. He says: "I’ve had my highest visions of Buddhist Emptiness when drunk."

There are lots of words of wisdom offered, lots of Buddhist concepts juggled and played with. As the book goes on Jack often seems confused by it all. It’s as if he thought nirvana would be as easy as two or three months of meditation. He begins to realize this is not the case, that his fate is inescapable, already mapped out - the Duluoz legend - with Buddhism just a temporary refuge.

A picture emerges of Kerouac, like Christ, just here to fulfill his destiny-to write "the ONE BOOK"---struggling and fighting against it at times, but really always just fulfilling his Fate. It’s interesting that this three-year Buddhist religious phase of Jack’s life took place in almost exactly the same years of life, early thirties, that his childhood Catholic Christ is said to have lived his public religious life. Jack’s imitation of Christ, best he knew how. He did alright and was a good writing Buddha for awhile, practicing dhyana, cultivating virtue, reading sutras, writing emptiness.

Obviously Kerouac was fascinated with all the words and concepts of oriental religion --- the six paramitas, the four transcendental virtues, the ten bhumis, crotopanna, sakradagamin, anagamin, kshanti paramita, and annuttara-samyak-sambhodi. Maybe all his Buddhism was simply stockpiling ammo for his wordslinger arsenal. In Buddhism Kerouac found new words, another language, new ways to say all the things he felt and knew. French, Spanish, English and prajna paramita. Always in love with the sound of language, Kerouac was knocked out by all the manomayakaya and acinty-paranima-cyuti word combinations he found in Buddhist texts.

And much of this time Kerouac is in actuality (in this dream of life) living with his mother and sister, brother-in-law and nephew in Rocky Mount, North Carolina and meditating in the woods with dogs---"long wild samadhis in the ink black woods of midnight, on a bed of grass." No doubt (and no wonder) his relatives got tired of all his Buddhist talk. It definitely was not all dharma and bliss. Read his letters of the same period. This is post-"On the Road", pre-"Dharma Bums" Kerouac, away from his wild pals, in quiet and serious study of Buddhism. But this period is getting him ready for the friendship and joy of "Dharma Bums".

I’m wondering if this is one of those books that will be more talked about than read. It is certainly a lovely book and a wonderful publishing achievement-as near as possible a facsimile of Kerouac’s original typescript. But for anyone without a strong interest in Kerouac or Buddhism, or both, it is a book they may not have the patience to read- 420 pages of Kerouacish ramblings on Buddhism. And the print is small. I can’t help but wonder if this book is more document than art. In editing Kerouac’s letters, Ann Charters has been accused of cutting too much. The editor of this book, David Stanford, may have to answer for leaving in too much. Perhaps a more readable book could be created by cutting some of the repetitive Buddhist ramblings. Or maybe a good publishing strategy would be to issue it in several smaller volumes, like the small Shambhala books on Eastern religions, or like R. H. Blyth’s Zen and Zen Classics. I think future editions might also be made more manageable by including an index, and perhaps a bibliography of Buddhist books that Kerouac was reading. For now though, we’ll be grateful for what we have. No matter what happens next I think it’s good to have the book issued first in it’s entirety, a mother lode that may be a long time playing out.

The book ends in March of 1956. Kerouac is getting ready to take off for Mexico again, then San Francisco and Desolation Peak and on to fame and alcohol in the remaining years of his life. Buddha Jack of the dogs and cats, not different from emptiness, listening to the sound of silence, in love with the sound of words. It ends with a picture of one of Jack’s angel dove ghosts, a truly amazing wonderful compilation book journey meditation on Buddhism and emptiness. Samadhis and Samapattis and Dhammapadda and Innumerable Aeons and Chilicosms of Blinkforths and Blablahblah wrote old Jack in his cups with a kitty walking down the path on the way that is not a way to the gate that is not a gate using words beyond words to express silence. Amen. So be it. Ainsi soit il. Thus it is. Svaha! Grah!

— Dharma beat

Bibliography

Autobiographical Novels

Visions of Gerard (written 1956, published 1963)

About Kerouac's saintly older brother, who died as a child.

Doctor Sax (written 1952, published 1959)

Fantasies of good vs. evil characters hiding behind trees and lurking around corners in Lowell. Interesting glimpse of Kerouac's childhood fantasy world and busy small-town life.

Maggie Cassidy (written 1953, published 1959)

Youthful porchlight romancing in Lowell.

The Town and the City (written 1946-49, published 1950)

Vanity of Duluoz (written and published 1968)

Kerouac's last published novel, a memoir of early days.

On The Road (written 1948-56, published 1957)

Visions of Cody (written 1951-52, published 1972)

More about Neal Cassady.

The Subterraneans (written 1953, published 1958)

Kerouac's pathetic love story about a black girl who dumps him for Gregory Corso.

Tristessa (written 1955-56, published 1960)

Junkie prostitute girlfriend in Mexico.

The Dharma Bums (written 1957, published 1958)

Desolation Angels (written 1956-61, published 1965)

Buddhist retreat in the Cascade Mountains.

Big Sur (written 1961, published 1962)

Satori in Paris (written 1965, published 1966)

A trip to find Kerouac ancestors in Paris.

Other Novels

Pic (written 1951/1969, posthumously published 1971)

Adventures of a black child in the South.

Prose Collections

Lonesome Traveler (published l960)

Excerpts and unpublished writings with a travel theme.

Poetry

Mexico City Blues (published l959)

Pomes All Sizes

City Lights Books

Scattered Poems (published posthumously l971)

Buddhist Writings

Wake Up, or Some Of The Dharma (written 1954-55, recently published in Tricycle, the Buddhist journal)

A straightforward religous biography of Siddhartha Guatama, the Buddha.

The Scripture of the Golden Eternity

A freestyle sutra -- check it out!

Other Prose

Book of Dreams (published l960)

Transcriptions of dreams.

Films

Pull My Daisy (1961)

Experimental film by Robert Frank, with narration by Kerouac.

Recordings

Poetry For The Beat Generation (1959)

With Steve Allen on piano. Short poems.

Blues and Haikus (1959)

Featuring Al Cohn and Zoot Sims. Haikus and other things.

Readings by Jack Kerouac on the Beat Generation (1960)

Unaccompanied. Poem fragments and prose readings.

— Dharma beat