An Independent Modernist

Karel Teige's "Minimal Dwelling" against contemporary Socialist architecture

After World War I, the experimental impulses of the first two decades of the century gave place to a period of social compromise in the European arts. In France, cubism evolved through styles like that of Picasso and the purists. These aimed to recompose the fragmented object in shapes inspired by knowledge and social action. In Russia, the avant-garde artists became engineers at the service of the socialist state, while in Italy the different trends of modernism competed against each other to become the official art of the fascist state. The appearance of Socialist Realism in the mid 1920s was to exacerbate this post-war élan - in many cases the political questions becoming not just a concern of the artists' but rather the very foundation of art.

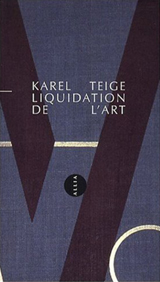

Karel Teige is an example of a theoretician whose aesthetic position was indistinguishable from his revolutionary political beliefs. He considered the historic distinction between traditional and modern art as being inextricably linked to the distinction between capitalism and Communism. However, he opposed Stalinist art strongly, not for subordinating art to politics but for betraying socialist principles by using architectural monumentality as an instrument of power to intimidate and repress the people.

As an active member of the inter-war year's European artistic milieu, Teige seems to have responded to socialist realism with the arguments of the avant-garde and to the avant-garde with the arguments of Socialist Realism.

Against the Grain

His political beliefs led him to an independent and critical position vis-á-vis the Congrés Internationaux d'Árchitecture Moderne (CIAM) and the Russian constructivist architecture throughout the 1920s. Teige shared the functionalist assumption that the building had to be a response to human needs. He recognised the achievements of Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and other CIAM members who sought to introduce improvements like central heating or bathrooms in working class dwellings.

He also agreed that the benefits of technical progress could be assured for all social strata by means of industrial techniques based in mass production, prefabrication and the industrialisation of the construction process. However, he argued that Gropius and van der Rohe's conception of pure functional design departed from an a-historical understanding of human needs that led them to propose an "objective" model of dwelling which, for him, in fact meant nothing but a cheap version of the family-based bourgeois house.

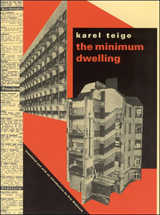

"Minimum Dwelling"

Instead, Teige conceived architectural function as a variable category linked to a social content in permanent change and proposed what he called "Minimum Dwelling", an experimental model of socialist dwelling thought to be developed in the Soviet Union at massive scale.

The theory of the Minimum Dwelling departed from the assumption that industrialisation and the political rise of the working class had introduced major changes in domestic life and that, therefore, architectural design had new functions to fulfil. The family had lost its role as an economic unit and, consequently, the woman had become emancipated and taken up employment outside the household. Accordingly, the traditional family house had to be redesigned, being divided into separate areas for each independent dweller and eliminating the marital bed, while collective laundries, canteens and kindergartens would take over the housewife's duties.

Teige vs Le Corbusier

It is precisely this understanding of functionalism that led Teige to oppose Le Corbusier and the Russian constructivists also. He accused the Swiss architect of imposing on his buildings an a-priori harmony of shapes that was not aimed at fulfilling functional requirements, but rather at the pursuit of an a-historical classicism for its own sake.

He foresaw that Le Corbusier's plans, when applied to low-income dwelling, would result in over-built states with an excessive density of population and a series of practical problems such as poor ventilation or lack of sunlight, derived from the superimposition of the classicist schema. On the other hand, Teige could see that Le Corbusier's elegant designs would become fashionable in the luxury market when enlarged.

At the opposite end of the spectrum of ideas, Teige believed that the emphasis of the Russian constructivists on the tectonic qualities and the assemblage of materials was something arbitrary and reductionist as it did not take into account needs other than physical ones. It therefore failed to enrich its findings with the science of human psychology in order to provide a broader architectural theory, something that Socialist Realism had done - though in a perverse way.

Leaving aside the somewhat utopian character of his Minimum Dwelling, Teige's critical attitude vis-á-vis both the CIAM and the 1930s Soviet housing schemes left him isolated during the early 1930s. He participated in several attempts to organise an independent network of architects, both at national and international levels, such as Léva Fronta (LEF) and the Europe-wide Association of Socialist Architects.

However, because of the lack of political counterparts and patrons these were short-lived initiatives. In the East, Stalin's trials were taking place and Teige's Trotskyism, as well as his deeply polemic attitude, prevented him from exercising any influence on Soviet architecture. In the West, the CIAM majority rejected the pressure to line up with any political doctrine and began to appear as an organisation for technical purposes.

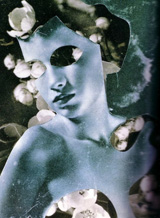

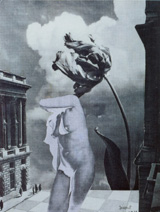

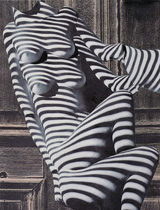

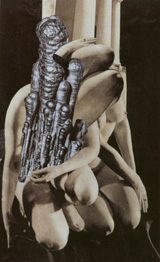

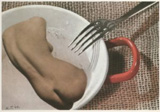

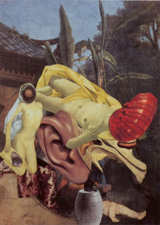

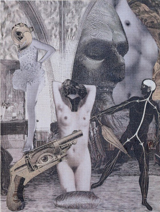

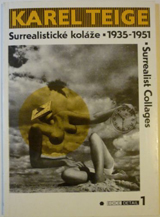

In Czechoslovakia, Teige was still an undisputed guru of modernism, but, due to his dogmatic attitude and the pressures of the CIAM, younger architects were seeking to break away from the country's isolation. All these events combined to bring about the failure of Teige's architectural revolution and eventually moved him to seek refuge in more evasive and less socially engaged activities such as surrealist photomontage.

Juan Gomez-Gutierrez

— Central Europe Review

The Style of the Present:

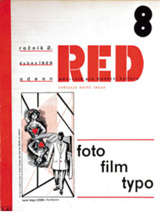

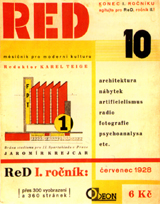

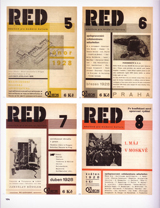

Karel Teige on Constructivism and Poetism

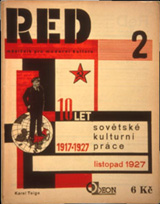

In 1929, Karel Teige —the leading theoretical voice of the Czech interwar avant-garde and a prolific critic of modernist literature, art, and architecture—published a review of Le Corbusier’s project for a world cultural center called the Mundaneum. Le Corbusier had every reason to expect accolades: Teige had been a tremendous admirer and had been enormously influenced by Le Corbusier ever since their first meeting in Paris in mid-1922. But surprisingly, Teige criticized the Mundaneum project as representing, in effect, a design for an avant-garde cathedral. Teige stated that "in its obvious historicism and academicism, the Mundaneum project shows the present non-viability of architecture thought of as art."

That in the late 1920s Teige should accuse the doyen of avant-garde architec- ture of practicing "obvious historicism" is striking, and Le Corbusier was clearly taken aback by the criticism. Indeed Le Corbusier could only interpret this charge as the implementation of utilitarian "police measures" against his own "quest for harmony" and aesthetic efficacy. Architectural historians, invoking less judgmental yet analogous categories, have represented the Mundaneum polemic as exposing a major rift within architectural modernism: George Baird, for example, has situated Teige’s "all-encompassing ‘instrumentalization’" within a general "shift of tone... toward a radically matter-of-fact and materialist conception of architecture...," and Kenneth Frampton has written of the opposition between Le Corbusier’s "humanist" modernism and the "utilitarian" radicalism of figures such as Teige and Hannes Meyer.

What such accounts overlook, however, is how Teige’s apparently strict and ungenerous evaluation of the Mundaneum was anchored in extravagant aesthetic claims Teige made elsewhere for Constructivism as the architectural "style of the present." The radical antihistoricism so prominent in Teige’s Mundaneum polemic was thus driven by equally radical claims about the historical status of Constructivism. That Teige’s merciless functionalism could be couched in such terms reveals a logic of historical nostalgia inhabiting even the most bracing rejection of historical precedent.

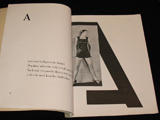

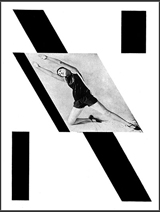

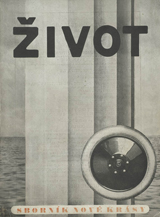

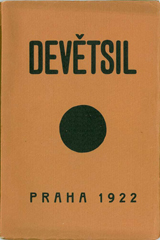

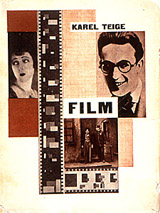

Teige’s copious writings in fields other than architecture, as well as the trajectory of his thought over the course of the 1920s, show a thinker more complex than the allegedly puritanical functionalist of the Mundaneum debate. For most of the decade Teige conceived Constructivism as only one ‘‘pole’’ of avant-garde culture, coexisting with a complementary principle he termed Poetism. Poetism—which during the twenties served as a rallying cry for Devětsil, the most significant grouping of writers, artists, and architects of the Czech 1920s avant-garde—proclaimed and celebrated the ludic spontaneity of modern life, drawing inspiration from mass cultural forms such as film, jazz, and circuses, and even from activities such as tourism and athletics. Whereas Constructivism had emerged out of the architectural critique of ornament (Teige named Gustave Eiffel, the Chicago School, and especially Adolf Loos as major forebears), Poetism invoked a critique of the traditional "descriptive" literary and visual image, a critique that Teige identified at times with mass cultural innovators such as Charlie Chaplin and at times with literary modernists such as Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarme, and Guillaume Apollinaire. Teige envisioned this dualism as the expression of a dialectical unity within a series of oppositions: rationality and irrationality, purposeful action and antiinstrumental Wohlgefallen, scientific functionalism and pure lyricism, and everyday life and aesthetic elation. The dualism was thus intended to reconcile fundamental yet conflicting positions within avant-gardist discourse: radical productivism (opposed to any understanding of aesthetics as independent of material production) with a liberatory aesthetic celebrating the release of pure poetic form. Like few other thinkers of the time, Teige directly confronted the daunting task of articulating an overarching theoretical framework for the disparate facets of 1920s avant-garde culture.

But this dual scheme entangled Teige in a series of logical contradictions. The contradiction that was most crucial here was not, as one might expect, any of the particular conceptual tensions between Constructivism and Poetism. Those tensions functioned more as the fuel for the dialectical engine: their combustibility was what kept Teige’s system moving forward. What ultimately revealed the route as a dead end, however, was the very structure of the dualism itself. For Teige’s theory of Constructivism centered on a critique of architectural historicism that identified a conceptual rift marring the integrity of historicist architecture: a conceptual rift that Teige (following Loos and others) felt took material form in the application of decorative layers of historical ornamentation on top of a functional structure that should have been deemed complete in itself. Given the importance of this critique of a "structure/ornament dualism" in Teige’s writings of the twenties, the appearance of a parallel dualism in the Constructivism/Poetism structure is striking indeed. Teige himself exerted considerable effort to avoid having Poetism appear as a decorative addendum to the severe teachings of Constructivism: effort that not only involved ever more laborious formulation of the dialectical unity of the poles but also drove him to articulate his Constructivism in ever more radical tones (as Le Corbusier would experience firsthand). These efforts, however, traced a vicious circle: the more radically Teige pushed the limits of Constructivism, the more insistently Poetism appeared as its ultimate promise—while at the same time the more difficult it became to justify this dual structure given the standards of Constructivism.

Thus, while the project of delineating a consistent theoretical framework for the avant-garde out of obviously incompatible principles perhaps displayed open utopianism, Teige’s utopianism was not simply the product of a theoretician’s greed. Rather, this utopian aim of reconciling the irreconcilable can be shown to issue from precisely the most earthbound element of Teige’s thought: his hard-headed functionalism. The prime interest of Teige’s dualist program in the twenties, therefore, lies neither in his formulations of Constructivism or Poetism taken independently, nor even in his juxtaposition or attempted dialectical synthesis of the two poles. Rather, the dualism is significant because Teige unwittingly betrays Constructivism’s inability to exist without Poetism. Poetism, the apparent opposite of Constructivism, was actually its inevitable logical consequence and would have emerged in shadowy outline even if it had not been explicitly articulated. The utopianism in Teige’s dualism was due to neither naive exuberance nor willful positing of a unity of opposites, but was rather the mark of theoretical consistency. The very purity of Teige’s Constructivism summoned its radical antithesis.

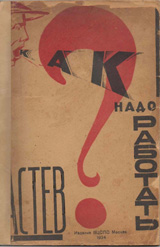

The genealogy of Teige’s functionalism reveals at the center of this dualist dilemma the very term that was supposed to guarantee Constructivism’s rigorous consistency: the notion of style itself. Only shortly before Teige’s 1922 meeting with Le Corbusier—which together with Soviet influences led to Teige’s articulation in late 1922 of a Constructivist program squarely within the mainstream of the international avant-garde at that time—Teige had been floundering in attempts to redefine and resuscitate the rather ponderous program of "proletarian art," which he had enthusiastically adopted in 1921. The slogan of proletarian art posited the nostalgic ideal of a soon-to-emerge "Socialist Gothic" that would end the perceived aesthetic "interregnum" by creating the stylistic paradigm of a modern folk art for the proletariat. Within a few months Teige had completely abandoned such rhetoric in favor of celebration of technological media such as cinema and photography, declaring the primacy of the machine for contemporary cultural production.

Teige’s adoption of Constructivism thus evolved from an early nostalgic longing for a new historical style that would give the present a standing equivalent to the great historical styles and to the Gothic above all. But the promise of Constructivism to create such historical standing quickly became predicated on its radical rejection not only of all traces of historical decorative systems but also of the very gesture of measuring oneself against the past. The ease of this inversion from millenarian expectations of renewal to confident optimism in the new suggests that the boundary separating historical nostalgia from militant hostility to past cultural forms is permeable. Teige shifted smoothly from a perception of the present as existing within a historical vacuum, with the consequent attempt to fill this vacuum by navigating some sort of reinsertion into the historical flux, to the perception of the present as being mired in a surfeit of historical detritus, calling forth the attempt to eliminate this surfeit through a radical clearing of the tables and a new instauration. The dualist dilemma—the insistence with which Poetism presented itself as the culminating product of Constructivism’s new instauration—thus represents the trace of this origin in historical nostalgia. Close examination of the logic behind this shift is instructive, for Teige’s dilemma is not simply the record of an error: it reveals and replays a paradox fundamental to the avant-garde thesis of a radical rejection of the past.

From Socialist Gothic to the Style of the Present

The claim that socialist revolution would create the conditions for the emergence of a new and all-encompassing artistic style—often referred to as a "Socialist Gothic"—was a common element of the rhetoric of proletarian art. In his earliest writings Teige used this idealized image to describe an art that would stand in some sort of immediate relation and be spontaneously comprehensible to the masses rather than to an elite only. He claimed that such a wide social grounding had been achieved most effectively by Gothic art:

In antiquity, Christian art was a secondary, derivative, immature style and only in the Romanesque period, when the break between the old and the new worlds occurred, did it expand to cultural and stylistic [slohové ] dimensions..., then to transform into the Gothic and so to develop into the most typical style. In socialist society, just as in the Gothic, there will be no difference between the ruling art and the underlying current of primary production. Popular [lidové] proletarian art will achieve the same power as that which created the Gothic cathedrals.

This image of the Gothic thus provided Teige with a model for the criterion of lidovost (popular character) that played such a prominent role in his understanding of proletarian art. At the same time it functioned as an image to hold up in contrast to the autonomy of art in bourgeois society. From this perspective, capitalism appeared as a force that had alienated art from its natural function by pushing it along a course of autonomous development and separating it from the everyday concerns and interests of the great mass of people. Proletarian art, by preparing the ground for a modern art that would be lidové, as the Gothic had allegedly been, thus promised a release from the constraints of autonomous art and a return to the direct interconnection of art and everyday life that had been deformed in bourgeois society. In this way, Teige implicitly linked the revolutionary action of proletarian art with a process of historical restoration. Proletarian art cleared the path for a return to the historical process of stylistic development that had been interrupted by the autonomy of art under capitalism.

The precedent for Teige’s use of the Gothic as a symbol of artistic and stylistic integrity, at least as concerns Czech influences, is easy to locate. The literary and art critic F. X. Šalda, whom Teige described in 1927 as the "founder of Czech modernism" and the "sign of a new era in our cultural life," had written in 1904 of "the new Gothic, an iron Gothic" portended by modern industrial structures. For Šalda, the Gothic was simply the most natural image for connoting the enormous potential for social cohesion contained in the true artistic styles. This strong definition of style (which Teige designated with the Czech word sloh, a word lacking the connotations of style as passing fashion or modish design often attached to the word styl) implied the power to reveal the various unrelated manifestations of a particular epoch as creating some sort of recognizable whole. In Šalda’s words: "Style is nothing other than conscience and consciousness of the whole, consciousness of mutual coherence and connection... Style is in conflict with everything that breaks this unity, with everything that takes up and isolates details from the whole, links from the chain, beats from the rhythm." The true styles, by linking isolated details into a whole, thus revealed a distinct and recognizable physiognomy for an entire historical epoch. Šalda’s emphasis on the organic totality characterizing such strong artistic styles, in its turn, recalled Nietzsche’s description, in the second of the Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen, of the ideal of "unity of artistic style in all the expressions of the life of a people." Through Šalda, therefore, Teige’s early exaltation of the Gothic as "the example of an epoch that is stylistic [slohové] beyond reproach" strongly echoed the ideal of an integrated, creative epoch that Nietzsche had held up in contrast to the weak, historicist culture of the nineteenth century.

Particularly important for Teige’s reception of this terminology, however, was Šalda’s association of this strong notion of style with a proto-Constructivist discourse. Šalda opposed the integrity of the true styles to the ornamental architecture of historicism and of much of the Czech Secession. A direction for modern architecture, Šalda insisted, would not be found in any new ornamental vocabulary, but rather in the strict logic of industrial structures. Šalda wrote of the power of the impression made "by a huge railway bridge, bare, desolate, without ornament, the sheer embodiment of constructive thought," and concluded that "the new beauty is above all the beauty of purpose, inner law, logic and structure." Since Šalda was first and foremost a critic of literature and painting, such an emphasis on the style-creating capacity of functional architecture is perhaps surprising. But this language almost certainly reflects the influence of Jan Kotěra, a former student of Otto Wagner and one of the groundbreaking architects of Czech modernism with whom Šalda co-edited the Secession journal Volné směry (Free directions) at the time. In this manner Šalda set an important precedent for Teige through his application of terms stemming from the discourse of early architectural modernism—in particular the terms "ornament" and "eclecticism"—to art and culture in general.

This ideal of the true style served as the context for Teige’s account of the failure of art in the bourgeois era. Bourgeois art had never succeeded in creating such a style, but the reason for this was not that artists in bourgeois society had been incapable of creating forms sufficiently beautiful or powerful. Teige had enormous (if selective) respect for the artistic accomplishments of the nineteenth century and often emphasized how groundbreaking many of those accomplishments had been. Nor did Teige, though himself a political radical, blame the failure to develop a true style on the absence of progressive political views among many of the most powerful or aesthetically progressive nineteenth-century artists. No matter how strongly the vision of an individual artist in the nineteenth century may have been motivated by concern for social issues or by outright socialist allegiances (Teige pointed to Gustave Courbet and Vincent Van Gogh as examples), no matter how brilliant may have been their aesthetic achievement, and no matter how pervasive was their influence on the later development of art, all such visions remained those of individuals. No vision was so powerful that it could succeed, through sheer persuasiveness, to force its way to lasting cultural dominance. The vicious circle of bourgeois culture was, indeed, rooted in the fact that it was precisely the aesthetic power of its greatest artists that perpetuated and deepened the most insidious feature of its art: individualism, chaos, and the simultaneity of incompatible visions. To "think" or "will" one’s way out of this dilemma was impossible. Every coherent proposal for a way out of the chaos simply took its place as one more monadic vision and thereby increased the chaos.

Teige’s explanation of this situation made use of a fairly orthodox Marxist argument. For a true style to gain hold, a minimum level of social continuity was necessary. Previous ruling classes had aimed to preserve the existing relations of production, which constituted the bases of their power. This resistance to change, disastrous as it may have been for the establishment of more just class relations, did produce fertile ground for art. It was precisely the social stagnation of prebourgeois societies that had produced the continuity necessary for the development of a true style. As Karl Marx had observed in The Communist Manifesto, however, the ruling position of the bourgeoisie was no longer based on preserving, but rather on constantly revolutionizing, the relations of production. For Teige, the resulting "overturning of production, ... creating chronic uncertainty and nervousness," and the repetition of cycles of overproduction and economic crisis, all resulted in an analogous "pathological acceleration of the development of modern art, which cannot settle on a definite form of stylistic expression." This was why, in Teige’s view, bourgeois art was ultimately condemned to a chaotic individualism. This was also why the emergence of a true style was contingent not upon strength of aesthetic vision but rather upon revolutionary change of the structure of society. Proletarian art functioned only as an anticipatory vision, or as Teige termed it, a předobraz; the true Socialist Gothic could only emerge out of a transformed society: "Style will only come with the establishment of a new social order." Artistic and political revolution were thus linked for Teige not merely by a shared spirit of rebelliousness —which was of course a dominant feature even of bourgeois art—but also by logical necessity.[...]

Peter A. Zusi

— eprints.ucl.ac.uk